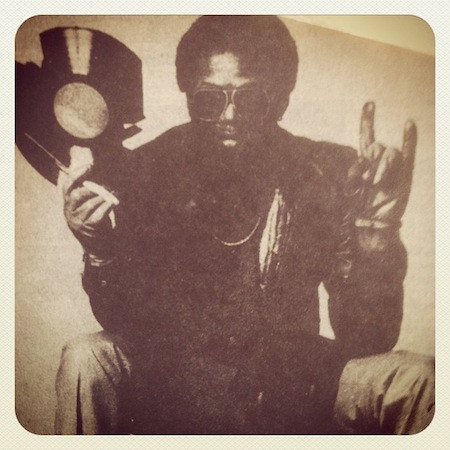

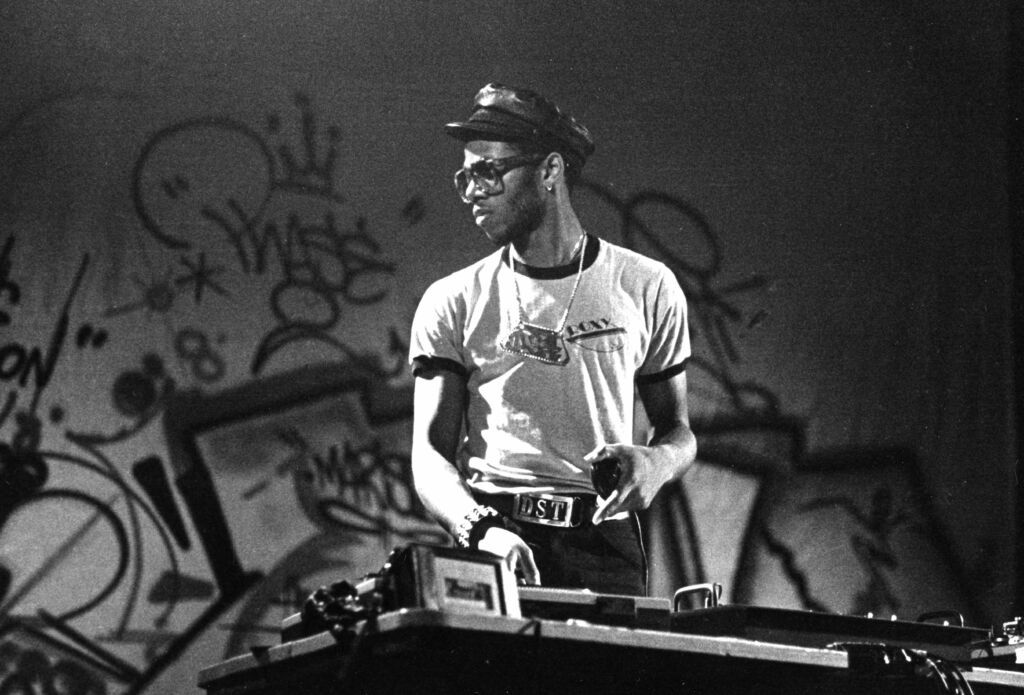

Grandmixer DXT scratched up a Grammy

DXT, Derek Showard, or Grandmixer D.St, as he was known back then, took the art of scratching from Bronx parties all the way to the Grammys, with his precision quick-cutting style making him one of the keystone pioneers of turntablism. After drumming in local funk bands he took to DJing at the first flowering of hip hop and built himself a following north of the Bronx in Mount Vernon and Westchester, together with his MCs the Infinity Four. He played with Afrika Bambaataa at the legendary Roxy nights, he was featured in Wildstyle, and he was part of the first hip hop tour to Europe. As the turntablist on Herbie Hancock’s global 1982 hit “Rockit” his was the first DJ scratching most people ever heard.

Interviewed by Frank in Harlem 7.10.98

How did you get into music?

I’m from a musical family. Grew up in the Bronx. My mother sings. She still does. She’s actually talking about putting together a gospel record.

Always gospel?

Nah, she was always singing blues and pop. Really blues. Billie Holiday kind of stuff. And my sister is a professional dancer. She’s danced as long as I can remember. So my whole family was in showbusiness.

How about you?

I always enjoyed music. I used to sleep in the living room on the floor by the radio. I’d spend a day just laying there changing from station to station. And instead of singing “The Love You Save” by the Jacksons, I would be singing “Benny and The Jets” by Elton John, songs by 10cc, like some longhair. The variety of music I would listen to was vast, I had an appreciation for all types of music.

And playing it?

I started off as a drummer. I had my first drum set I had to be five, four, maybe younger. It had one of them British rock groups on the bass skin, like the Beatles or something. When I got into school I learnt how to play the clarinet. I was trying to play every instrument. I would borrow someone’s trumpet and sneak into the orchestra rehearsals, and the teacher’d say, “Are you in my class?” And I would just play, and I’d hit some of the notes. I would do just as well as anyone else in the class. And I noticed something about playing the horn. It’s a feeling. When you’re blowing it’s what you feel. You can actually play it if you feel what it feels like to get those sounds out.

Instinctive?

Yeah. It’s an instinctive thing.

Were you always DJing as well?

No. I played drums for a long time and in my neighbourhood all the musicians were older guys, and they would only play jazz. I played with these guys and I would always want to play some of the more hip stuff that was on 99X radio station, a rock and pop station. So I would only be allowed to play with them if I was gonna calm down and just play some shuffle beats. Just vibe with it, so I couldn’t play no beats. Right around ’74 I was playing jazz in the summertime. In parks all around the Bronx.

What were the names of the bands?

No name, just neighbourhood musicians. They’d bring out the amps and just play outside. I became a roadie for a band called the Funkmaster’s Gang. This was a cover song band from Mount Vernon. They would do all the hottest songs. I was their first and only roadie. They were doing these local little gigs and talent shows. I would carry the cables, wires, drum parts, use a vacuum cleaner to blow dry ice on the stage.

We did a party at a Latin club and there was a DJ there when the band wasn’t onstage. He was just playing some old classics. Bobby Byrd, “Keep On Doing It”, and at that time that record was old. But just the way he was playing I thought it was pretty impressive. And to this day I don’t know who he was, but that was the first time I saw a DJ.

And then a friend of mine, James White, I called Jazzy. He was telling me about this guy Kool Herc. “Yo man, Kool Herc’s doing a party, we gotta go.” I went to see Kool Herc and I realised he has the same kind of pull that the bands have, you know the local bands. People go see him just to see him, and I just stood there and watched him DJ and I was amazed. And he didn’t cut on time or nothing like that, he just, his variety of music, the songs that he had, it was very clever. And it moved the crowd. It was a combination of the old and new and stuff that wasn’t even released yet.

Where was this?

I went to see him at The Executive Playhouse. In ’73, ’74.

At that stage he wasn’t playing breaks?

He was playing them but he wasn’t cutting. Kool Herc never cut. To this day, he don’t cut, he never cut records. Maybe most recently before he completely stopped, he may have started cutting beats on time, but back then he would play something and when the break would come up he would just move it on. He would just pan the fader over, it would be all off beat or whatever.

So he would play the breaks without cutting.

Yeah. he would play the breaks without being synchronised.

Even in ’74 he’s playing breaks after breaks after breaks.

Yeah.

Was he playing two copies of the same record?

Yeah. yeah. So he’s actually the first guy who did that. But Flash made it to the point where he would cut them so it’s more of an edit.

On beat.

Yeah. I stood there, and at the time I was a B-boy, so you know I was ready to breakdance at the drop of a dime. So I’m listening, checking out people doing the hustle, and I’m waiting for “Apache” to come on, so I could B-boy. And I’m checking out Herc. And I’m also in there breakdancing, and so he gave me the opportunity to just go there and work on my moves. So now there’s a place, there’s a guy I can go, to his party and practise my skills. Whereas anywhere else you’d just be waiting for the breaks.

So would you just be standing on the side?

Most B-boys would be like this [adopts the b-boy stance]. That’s where that came from. Just waiting for the break part. Not from trying to be cool.

You’re just waiting for the break.

Yeah, you’re just standing there waiting, you know… while the hustlers are doing the hustle and you’re standing there like this.

And then the break comes on and then bang.

Yeah, and then you’d be doing circles.

B-boying pre-dates everything. It’s before people were playing just the breaks…

Yeah, because it’s a part of dance.

When did that whole thing start. People waiting for the break, and doing those uprocking moves?

That’s thousands of years old. Just like rapping. I could pull our records of Pigmeat Markham from the ’50s. And they rappin’. I seen tapes of African tribes, man, they breakdancing, man. That’s where it comes form, man. To think that we just made it up, that’s absurd. It’s a part of who we are; it’s in our genetic make-up.

So you have a bunch of guys who are waiting for the breaks, and then you find this DJ, Kool Herc, and that’s all he plays.

Right.

There must have been a lot of guys like you who thought, wow, this is my DJ. I’m gonna be here every time he plays.

Right, so that’s what happened. And sometimes he played the disco for the disco crowd. Then all of a sudden he would play the beats and it’s B-boy time. And some of the best hustlers [as in the dance] were some of the best breakdancers too. And back then it was still into, you know, asking a woman to dance. With some class. And now you can impress her by doing a spin on the floor. It was a great time, man. So that became it. I became a fan instantly, of Kool Herc. So ’74, ’75 I was going to Kool Herc parties. And I started going to Flash parties.

Just how legendary were they at that stage, in the Bronx?

I mean, these guys were famous, man. They were incredible. And my mother had all them records so I started stealing her records. And making little tapes and blasting my music into the neighbourhood. So in my neighbourhood, I was like the Kool Herc guy, cos I was the only guy with all those records.

So you’re DJing from around ’76.

Yeah. It took me a while to get a pair of turntables. I think it was ’77, I hooked up with some guys who had turntables. Before that I was making pause-button tapes. And since I was a drummer already I already knew about synchronising time. Back then you had to put the tape deck halfway in record and hold the record button so it toggles enough where it’s past the point where it’s not locked out. I was already cutting, I was already cueing. I think that helped me a lot when I made the transition to turntables, I already had that skill of being on time. I had pause button tapes all over the place. Everyone had one of my pause button tapes. I was one of the biggest pause button guys. And I did not use a pause button. Nah. I would just cut with the record button halfway down.

Did you sell them?

I was just giving them away. Sometimes five bucks. When I got a tape deck with a pause button I was off the hook! Dnn, dnn, dnnn dnn. Then we started making plates, acetate plates.

When did that start?

It was going on for years. We just got hip to it in the hip hop day.

Herc and them made acetates?

They made plates, yeah.

What gear were you using to DJ?

It was ’76, the bicentennial year actually. I was hooked up with two other guys, Shevin and Timmy, and they had two Gerrard turntables and a mixer that had four knobs. It was a mic mixer. And we started putting our records and stuff together. People were already calling me DST, which stood for D. St. I got that name cos I used to hang out on Delancey street downtown. People would say “DST – Derek, Shevin and Timmy.” but really I was D.St. which was D street.

So we started doing house parties, and we would literally have to be in a room so quiet so we can hear the record cos there were no headphones. So we would put our ear to the record, to the needle while it was playing. To cue up the next record. Like “Shhh. be quiet” and you could just hear the “ch ch chsh chush” and…

What? You’d be in another room?

Yeah, we’d be in another room. And then we’d turn the four knobs, and mix, and then that went on for a while. And then those guys got with one of the neighbourhood thugs, who had the most equipment, cos he was trying to DJ too. And I just wasn’t into the rough guy scene so I started doing parties myself. My first party, as DST, by myself at my friend Charlie Hollingsworth’s private house, in his basement. I think that was ’77 or ’78. It was somebody’s birthday. I hooked up with some of my old friends I grew up with. They had some Technic turntables, I was still borrowing people’s stuff. I was a poor guy, man. I just had records. I would always have to use somebody’s mixer, somebody’s turntables.

I started going to these parties up in Mount Vernon, and I got popular up there, from dancing. So I was “Yo, I DJ, man. I got skills.” And I got in with the big Mount Vernon DJs, Rob the Gold, and his Brother DJ Smoke from the Kool Herc crowd and another guy called City Boy. They had big 18-inch woofer cabinets, and so I’m really playing on a real set now. They had 1800 turntables. the Technics, the real big heavy ones. A real mixer, he had all these records and I brought my records up there. So now I started really cutting.

And I was still going to check out Flash. And Bam. My friend Booski was tellig me “Yo, Bambaataa lives down the block man, I went by his house, he wants to meet you.” Cos I was making my own noise in my own neighbourhood, and there was also DJ Breakout up there too. So I went down to Bam’s house and we both sat there for about a half hour, nobody said nothing, then we just started talking, sitting on his balcony. It was like “Yeah man, I heard a lot about you,” and yeah, I heard a lot about you.”

Bam, Herc and Flash, those were the three guys. I got inspired by each one of them on a different level. Herc overall, just being a DJ and being able to have the ability to pull people like a rock star. Flash was being a technician, and Bam had the most impressive collection of music. I mean to this day no-one comes close. And his insight in a club. he could go into any club. There could be two people on the dancefloor, put Bam on for an hour, the whole floor is packed.

What was it like between the three of them?

There was always rivalry. They were friends, but there was a rivalry. And the whole thing was, in hip hop culture, if you was hot and you was doing a party on this side of town, then everybody’s going. The second generation of DJs would have their own little crowd coming to their thing, but then the major clubs, the major crowd would go to one of the big guys. If Herc was doing a party it didn’t make sense to do a party three blocks away. You’d have to be way over on the other side of town. Like Flash is way on the other side of town, doing a party. Or in Harlem or somewhere. You couldn’t be in the same vicinity. Everybody knew that if you went to Flash you gonna see a technical show. If you go to Herc, you gonna see this huge system, magnitude five on the Richter scale. When Bam goes, you gonna hear records you never heard in your life, that’s gonna get you movin. You know.

Did they have different styles in terms of MCs?

Flash was the first guy to have standalone MCs. Herc used to play sittin’ down. He would be sitting with a mic, an echo pedal and a microphone, and talking and playing. Each DJ would sit in. Coke La Rock would sit down, with his mic. Clark Kent, they would just sit there, and they were cool.

It wasn’t like a stage show, they were behind the decks?

They were behind the desk. Herc would be sitting there, with the mic on a boom stand, and looking through the records. “Check it out y’all, we gonna do a sure shot, one time.” And Flash, he was a technician, so he had to stand. And he didn’t have time to talk. Bam is standing because there’s so many records coming at him. Bam normally has this little dance he does, too, when he’s DJing. So he’s not gonna be sitting down.

And what about MCs?

Cowboy was the official traditional hip hop MC. He’s the first. Unfortunately he’s gone. But he was the first, and I’m talking standalone, standing beside the DJ. Toasting – is what they were actually doing.

Bigging up the crowd.

Yeah, the MC was the guy who comes out onstage, “I’m your host.” The Master of Ceremonies. Cowboy was that guy, he was the first guy: to be an MC. And he started the “Hip hop the hip-hip hop hip hip the hip” Cowboy! The story goes that a friend of his was getting ready to go into the service. And he was saying “When you get in there you’re gonna be going “hip hop the hip hop, hi hip hi , and you don’t stop.” and everybody was OK, yo!” and that’s how the story stuck. True story.

The other story is that it was Lovebug Starski.

Cowboy! Cowboy started all that. Lovebug Starski took it and made it the thing of the day. He expounded on it. Cowboy started it.

When did you start taking DJing a bit more seriously?

Those guys Rob and City Boy up in Westchester, they didn’t know nothing about Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, or Kool Herc. They were still straight up disco. When I went up there, I got these beats. So I’m like Kool Herc now. So when people would come to our parties, when I’d get on I’d start playing these crazy records, and people would be like “What are you doing?”

They didn’t get it

They didn’t get it.

So you would clear the floor?

Yeah. I would clear the dancefloor. Until the people started going “Yo, that’s the old… Yo, I remember that song.” And then I started mixing it up, and then I had a big big following in Westchester.

How long did it take?

Took a summer. One summer. Once the women got into it, that’s where the guys are gonna go. Then that was it, they caught on to the hip hop thing.

What were you calling it back then

Hip hop. I mean we wouldn’t say hip hop, but that’s what it was. We would just say we’re throwing a party. We didn’t talk about culture or anything, we just said hip hop because that’s who we were. When you’re in it, you don’t really talk about it, it’s just music.

When did you start thinking you could take it maybe another step further?

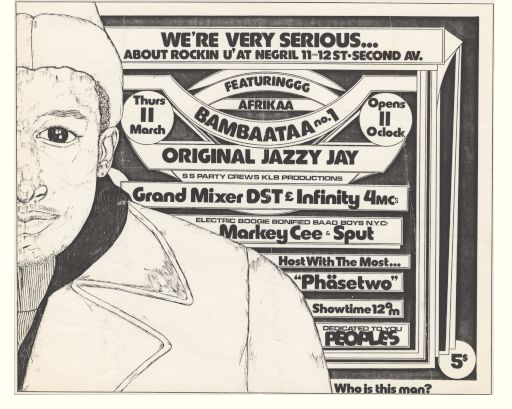

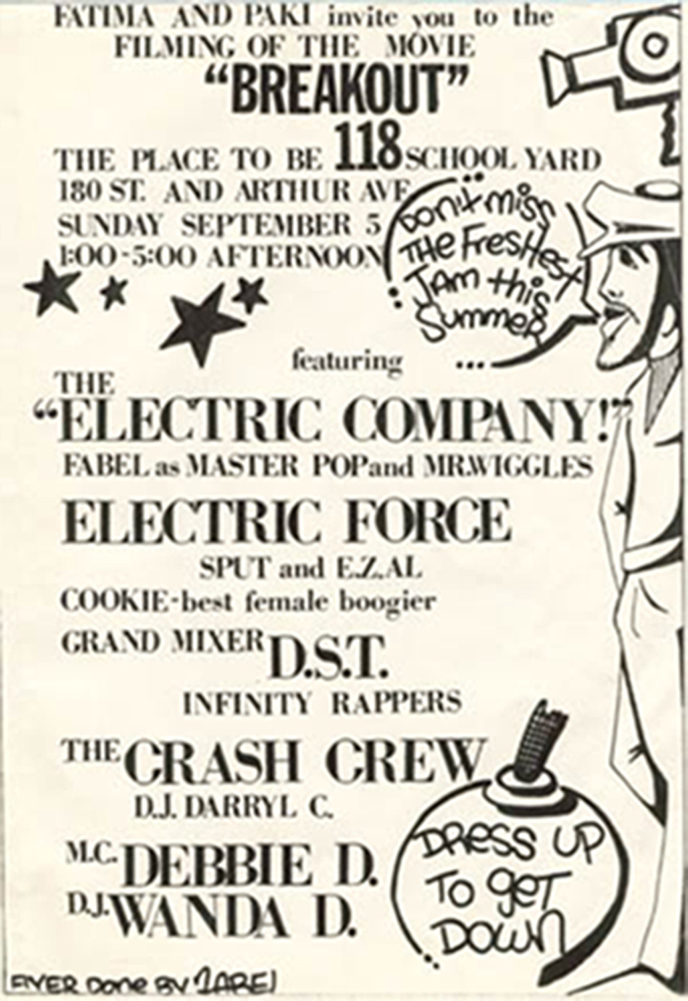

There wasn’t no groups during this period. And then these groups started coming up. Furious Five, and so on. So I said I gotta get some MCs now. I had Baby T and Baby Ace, two girl MCs. Then I had the Infinity Three MCs. Baby T, Half Pint, Kool Out. I actually have a flyer. I think that’s ’78. I have a flyer of that. And I went to New Rochelle, and the crowd thought I was insane, because I had people up on the table, with mics, “Yo, man, this is the B-boy thing, man. Whatch’all talking about?”

And so now we’re in high school, We were all saying rhymes. And I met this Raheim from Furious Five, he was there, all of us was in the same school, so he’d come up and we would just make these tapes, of us cutting and rhyming. And I said “Y’all want to join my group?” So now I had the Infinity Four MCs, when we really started hiting hard, making noise. It was me, Shaheim, Mike Nice, Kimba, and then we got this kid, Baron. Baby T had got fired. Shaheim wasn’t feeling her. And that was the one that blew up. Me and those four.

And then I had a guy named Little Quick, he was my understudy, I taught him how to cut. And then we had this little little white kid named Joe. He was a little boy, like nine or ten, and he was no joke. I used to stand him on a milk crate to DJ. He got a record store in New Rochelle now. We used to call him Big Joe. People used to see us with this little white boy and they’d be like “What the fuck. What are y’all doing?” Then it was like “Watch!”

So it was the three DJs, and Kool Aid, who was the master of beats. Bam is the Master of Records, but Kool Aid was the master of beats. Even Bam’ll tell you, this guy had a gift for it, ’cos he would read album covers, and he would look for specific percussionists, specific drummers, and he knew how they played. So whenever he would see those names, he knew that there’s gonna be an ill beat somewhere, He would spend his entire day, and night, in the Village, going through records after records after records. And he worked at an ice cream parlour outside Madison Square Garden making sundaes all day long. And he’d leave there and go to the Village to find records. That’s all he did.

And he was playing with you?

Yeah. I had my whole entourage, it was Kool Aid: Master of Beats, Little Quick, Big Joe, Infinity Four, which was Shaheim, Baron, Kimba and Mike Nice, and Jaheim, who was the programme director. He would keep all the records in order and pass me my records. We had a whole synchronised thing. I would never look backwards, I would always go like this [mimes being handed a record from behind like it was a relay baton] And I was so fast at it they were like, “Damn, look how they work.”

Your style was just to play beats?

I had the traditional disco DJ blending skills. You start there, you have to have that. But then the more radical things were the most demanding, so you practised them more…

Take me through a typical show

I was the DJ at the Roxy, which was the biggest scene in New York, and the way I would do that is I would start out by playing the typical stuff that you hear on the radio, and some of the club stuff. And then all of a sudden I’d just twist the whole club. I’d throw on “Stop The Love You Save”, by the Jacksons, from the beginning with the drum and horn intro, and the whole club would go “Oh shit!” and then from that point I’d go left, completely go fucked up. And that’s what I went after. And that’s what makes hip hop so special. Because it’s a combination of everything. Hip hop is the only music genre that’s everything. I mean we would throw on Elvis, “Love my baby, and my baby loves me” [“C’mon Everybody”], that’s a hip hop classic, know what I’m sayin? And “The Name Game”, and all these old songs. These are songs that you’d play in a hip hop club.

It’s the way you’d combine them.

Yeah, you could be playing “Don’t You Want Me Baby” by Human League, all of a sudden you’d throw on “Shoe Shine boy” by Eddie Kendricks, and the club would go crazy.

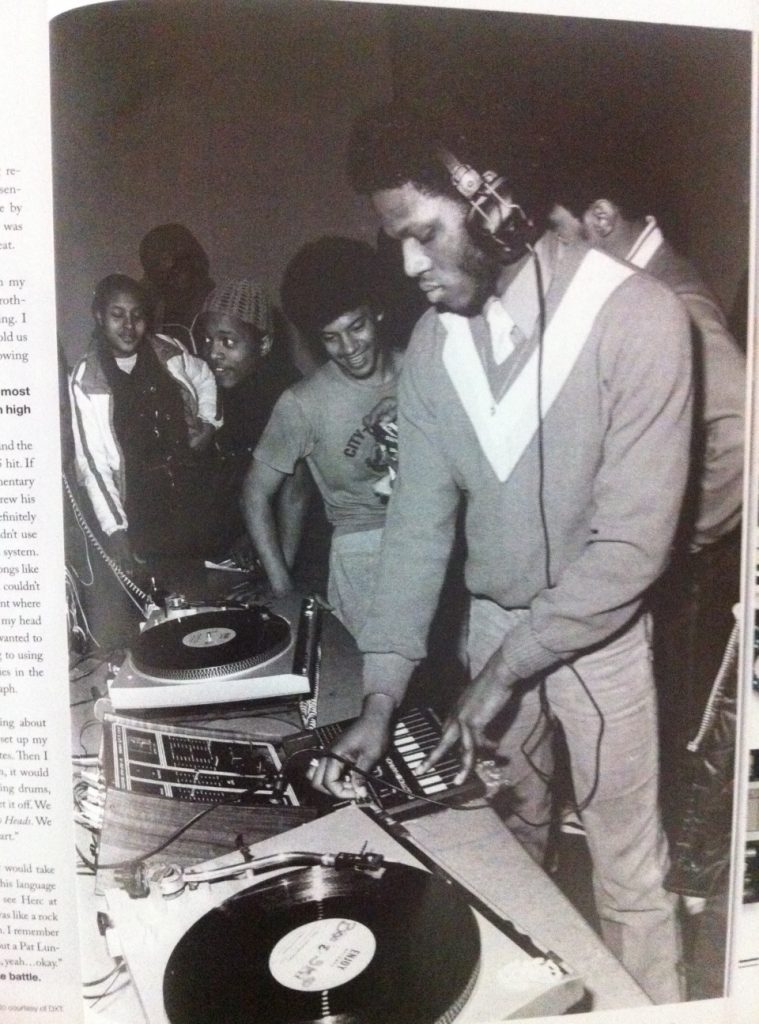

Tell me about scratching. How did that come about?

There was Flash and Theodore, and another guy who doesn’t get no credit, DJ Tyrone from Cool DJ D’s crew. His DJ, his hip hop DJ was a kid named Tyrone. And he used to take “Apache” and he would go “Dmm-zmm, dmm-zmm, dmm zmm.” [ie scratching just once, back and forth] That’s all he would do. But it was so dope because nobody ever did it. And then he would go [he lets the beat start, then catches it again for another scratch]. That’s all he did, but it was enough to go “Ohhhh shit” And then Theodore, who was phenomenal, and he was a prodigy. He was so skilled so young, it was ridiculous. It was effortless, his cutting ability. I mean, he was faster than Flash. Flash will deny that, but he was faster than Flash. And he was articulate with the shit. Physically, you know.

What do you mean?

He expressed it. Without opening his mouth, he was physically articulate, in his gestures, and in his ability to be so precise, and synchronise. Flash was good, and Flash was a definite technician, but there was something about Theodore that made him different. And remember he was a student of Flash. He had this knack for speed, and to be on time. What I mean is, it was articulate for me, cos I’m a DJ and it was a language I understood. It may be esoteric to most, but I understood it.

And what sort of things did you start doing?

There was a whole system I would have from one record to the other [he mimes a show where he’s changing records over and over without looking behind]. I would never look back. Never ever would I have to look back. And sometimes when I would do tricks, he would have to put records between the feet of the decks. So while I’m playing this one, boom, I hand him that one, he takes one, he hands me one, he sticks the next record under the turntable. So I go like this [he demonstrates changing three different records] And sometimes we would do tricks together so Little Quick would come over to the turntable and he’d have his little group of records, I’d go Poww and he’d grab the needle and go poww! and I’d be on this side pow, pow pow [playing side by side on two decks]. We would do crazy shit, like I’d spin around and he’d take over, and then bam and I’d walk away, and he’d go to this turntable, wham, wham, and we would just keep circling and circling, and then we would do it switching records. It was all synchronised shit. And that’s what made us real popular. Cos like I said, I’m one of the children of the three guys: Bam, Herc and Flash.

And this grew into scratching.

As a musician already, I started using my music skills to manipulate the turntables. And so I started forcing the whole threshold of the concept of being a turntablist. All of a sudden I was doing all this insane stuff, and people were like [an amazed nerd] “He did that with the turntable!” And so people started really really focusing on it and realising you could do shit with the needle on the record. It was all kinds of stuff. Like needle dropping. It almost doesn’t happen no more. But the most talented, the best DJs are the ones who can needle-drop, on cue, at will. [put the needle exactly on the start of the song by eye]

That’s what everyone says about Theodore.

The best, Theodore… There was only three or four of us that mastered it. There was me, Theodore and Imperial JC, who were the best needle-droppers. And believe it or not, Little Quick mastered it, it’s just that he didn’t get the recognition, cos he didn’t get out there. But he was one of the best too. Flash was not one of the best needle droppers, that’s why he started the clock theory, spinning records back, cos he couldn’t drop.

JC was the fastest out of everybody. Out of everybody. JC was the first person to catch it like “Good, good, good, good…” with “Good Times”, he was the first person. “Good, good, good, good, good, good, good,” Cos I was still going “Good times, dum dum, good times, dum, dum…” and I got this fast “Good times, good times, good times, good times,” I mean precise. Cos when JC did it that fast the shit was all crazy and out of time, he still did it. I remember the first night I seen him do that and I went [sharp intake of breath] “I gotta go home and practise.” And he did it on Herc’s turntables. That’s when he was spinning for Herc.

And that was the whole thing about the hip hop culture. Every time you went to one of the parties, you never knew what to expect from one of the real premier DJs cos they was always home.

And look at what turntablism’s become.

These new DJ battles, every time I go, now it’s off the hook. I look at these guys and I think, “We started that shit.” It’s incredible these guys, what they took from us, and there’s no end to it. I love to go there and see these guys. Me and Flash at the DMC [mixing championships], we was sitting there going “Yo man, look what we did. Look at this, man, this is ridiculous.” To actually know that you have inspired a genre, a whole movement, and we were just in the projects, doing that, with no money, just for the love of it, man. And now that shit is incredible. I should own a piece of fuckin’ Techics turntables, you know what I’m sayin? The amount of publicity and promotion that I’ve done for them.

When did you realise you weren’t just a DJ any more, you were using the turntable to be an artist?

Took me a while. You know when I really felt it, when Quincy Jones came and sat in front of me, took a chair, spun it around backwards and sat in front of me like this [chin on folded arms intently observing] . This close [about two or three feet away], turntables right here. “Go ahead, play.” Just like that. And when I finished he picked me up and gave me a bear hug, and walked the fuck out. Then it was official for me. Even at that time, my whole band had no respect for me. I was stood thinking, damn, these motherfuckas don’t want to give me no props, man. But when Quincy said “Yo man, that shit is dope. That’s some dope shit you doin, that shit is so bad, it’s incredible.” He was talking music. He said “You playin’ triplets. You playin’ a lot of triplets.” I was like, “Yeah, I play triplets. And also Narada Michael Walden, same thing, he came backstage after one show and he said, “Man, that shit is so incredible.”

This is when you’re working with Herbie Hancock?

Yeah, The Rockit band. It took up to that point, for me, as a musician, those are my peers, so I want them to respect me. I know the hip hop crowd loves that shit. But that was my way of knocking on that wall. At that time, they thought rap was dead, it’s gonna die, shit’s over, and then here I come, with this shit, knocking on the door, yo let us in. And I was the first guy to get to that door.

How did you get hooked up with Herbie Hancock?

Playing at the Roxy. I met a guy named Jean Karakos who owned a French label called Celluloid. Barry Mayo from Kiss had approached me to do a radio show, and I was like “I don’t DJ on no radio. That shit is crazy, man.” Something about it bothered me. The confinement. I can’t keep a job, cos I can’t follow orders. I told him check Jazzy Jay and Red alert, and so they ended up on the radio. WBLS.

A guy named Bernard Zachary became my agent, he said, “These guys want to give you three grand a night to play at this club called The Bains Douche in Paris.” And I was like… “I’m gone.” I went and got me a passport. They said yeah, man, matter of fact the Rolling Stones are doing a video, they want you to be the DJ in the video in Paris. They’ll fly you out there tomorrow. It was ridiculous. Plus the Roxy. Plus I was playing in another club called Armageddon on Wednesday nights in the Village and I was getting a grand.

Larry Levan was the number one DJ but all of a sudden, all of these guys from Bonds International Casino, all of these DJs one night, came to the Roxy cos it was like, “Who is this guy and what is he doing?” I also played the synthesiser in my set.

When you opened the Village Voice they had all the clubs, and once I got New York’s number one DJ, I was off the hook. And you can demand prices. I was also very aware that these people were making millions of dollars. And that’s how my fallout with the Roxy came about, which was the biggest club in America at the time. At The Roxy I was getting $2500, and that was for the whole weekend. To three grand for both days, so that’s 1500 dollars a night. I wanted a dollar off the door. One dollar. That’s all I wanted. One dollar. They sell their liquor out every night, and when I would go away, Bam would spin there, or [Afrika] Islam would spin there.

Islam was the guy brought in to replace me. And I told both of them, “Look, we have to stick together on this. They’re making millions of dollars. If they do not give me what I want, they can’t call you.” Of course you know that didn’t work. So I ended up leaving because they were making so much money.

How did your scratching develop?

By that time I was off the hook. I was doing all kinds of crazy tricks and stunts. I did everything but blow up the turntable. I was running around the place, coming back, and cutting on beat with no headphones on. Breakdancing, kicking the mixer, everything.

When did it develop to where you’re just using the record to make notes. When did you start doing that?

Let me just try to chronologically explain it to you. I was at my place. I was practising, and when we were just doing “chzzum chm, chzzum chm”, the simple stuff, it was just a matter of time before we’d want to do something more intricate. So as a musical person I decided that I can play rhythms, because I’m a drummer. But the idea of getting more complex than just “chzzum chm, chzzum chm”, that was an accident. One day I was doing my thing and I fucked up and Shaheim was like, “Yo, yo, that was dope!” I was like “Do what? That was an accident.” “Well do it again.” So I did it again, and it was dope, so I just started practising doing it. It was “drit dru drit; drit dru drit drrrr” [much faster and staccato than before] Just that “jig, jigga jic; jig jigga jic” where before it was just “jja, jja, ja, ja, ja” [the difference is we’re now hearing the pullback noise as well as the choppy forward scratch.] And so now it had more life to it and I started to practise that, [imitates a complex scratch which matches a breakbeat pattern], and I’m thinking, [more complex drum patterns], and now I’m humming it. Once I realised that there was something there, my musical skill kicked in and I started singing these phrases [sings funky percussion beat with a slight tune] And I started practising whatever I sang, just like when I played. And I applied my drum skills to the turntables.

And you’re going out looking for records that worked particularly well?

Right. I started recording my first single with this label Celluloid, and Fab 5 Freddy did a record with them called “Change the Beat.” And at the end it has, “This this stuff is really fressshhh” [the famous whooshy much-used sample]. So when we were doing “Rockit” I was going through a bunch of records to find the sounds I wanted. It was me, Bill Laswell, Mr C, my friend Carter, and Michael Beinhome, Martin Beesy, Booski, the guy who introduced me to Bam. We’re all in the studio and I’m doing my rhythms, and I used the fresh part “wisht wshht” and everyone went, “Woah! That’s it, that’s it, roll the tape,” and I just did my part. I just did whatever I felt.

That was original to Freddy’s record, it wasn’t a sample of anything else?

That was original to Freddy’s record. So I went [he does the scratch from “Rockit”], and I was just doing my thing.

Your single “Crazy Cuts” was after Rockit, yeah?

I had originally done “Crazy Cuts” before. A lot of people don’t know that. “Crazy Cuts” was a concept I had even before I had met Herbie, or Bill or any of those guys. And once “Rockit” became a big hit I went back to it and said, well let me try it again.

But you used the ideas that you’d developed in Rockit?

Right. The sound. I used the sound. But the idea of doing a record like that, that was old, before I even did “Rockit”. I did a few. I did one called “Scratchomatic”, I did a whole album of tracks which were just scratch solos. I have cassettes, man, “Scratchomatic” was so dope too man, oh my goodness.

Did you right away think “I’ve made the turntable into an instrument”?

Yeah. By the time I got to the Rockit band I realised there was something special, with the turntables, and it was growing. But like I say I didn’t really feel the respect from the band yet. They kind of looked at me like “You can’t have a turntable in a band, man.”

They thought it was a gimmick.

But there were people like Quincy, you know, big names [who thought otherwise].

What about Herbie Hancock himself?

Yeah, when Herbie saw it, because Herbie, he’s totally into that. Because it’s new, it’s clever, it’s technical.

Did he hear you play before the project came about?

They brought him to the Roxy. And they said this is the guy we’ve been telling you about. I didn’t meet him that night. I didn’t know he was there. They said we didn’t want to disturb you, so we was in the VIP room, just watching.

He was open-minded enough to say, I’m gonna make a record with scratching on it.

Yeah. So, we did it and made history with that record. That was a great experience, That was my introduction to mainstream showbiz, and to be introduced on that magnitude, was incredible. Booom, hit record, world tours, the Grammys. It happened so fast. “What happened?” “Yo man, you got a hit record.” I never saw the effect the record had in the United States, ’cos I was gone.

You were touring, supporting it.

I never was in my neighbourhood to see how people responded to it.

That’s a shame. People must have told you though.

I was in and out, so I would see a few people. In those neighbourhoods people are poor, so they think you’ve made it, so now you can’t talk to nobody, so everything gets real funny. I just became so busy that your life just changes.

How long were you on tour?

From ’84 to ’88. And when that band ended and I was in the Headhunters, playing keys, and singing lead by that time. And turntables. So I took the ride, you know.

What was it that made the band respect you as a musician?

Just one day, it was a song we were working on, there was some trouble at rehearsal, and they were asking Herbie – “Hey Herbie, this part?” And he said “Yo man, don’t ask me, ask him, he did the damn song.” I’m a musician, man. I understand it. I can get with a bunch of musicians and have them play something, and that’s the way we did the songs.

As a DJ was it natural to move into production?

I would say, as a musician it was easy to move into DJing. And so production was a normal path for me.

Do you think a DJ has a special insight?

Some. I know that my DJing experience helped me to get better insight on music. On the different processes people take to create their music, and different cultures of music. We go out and get polka records, man, country and western, all genres… Because in hip hop it’s everything. It’s whatever you can turn and twist and mould into the rhythms of the day.

© Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton