Andy Votel digs for wrongness

Interviewed by Bill in Marple Bridge, October 2022

He’s one of the most inspiring collectors you could meet, digging deep in the vinyl mines for accidental masterpieces. His reissue label Finders Keepers is a parallel musical universe, and has had Nas, Madlib, even Jay-Z queuing up to source beats from it. But Andy Votel didn’t much like music to start with – not until he heard it hacked into breaks and samples. For the latest release on his hip hop label Hypocritical Breakdown, he’s returned to his lifelong craft of rapping for an album of his own beats and rhymes, under the name Violators of the English Language (VOTEL in case you hadn’t twigged), which is a crew name that dates right back to his “kamikaze rapping“ childhood.

Violators of the English Language is essentially you being an artist, and that’s something you hadn’t been for a while.

It took something as crazy as lockdown to actually think, well, we’ve been saving this potential project for a rainy day. Like, a very rainy day. A rainy day where you’re not even allowed to leave the house. I essentially rung six or seven mates that I used to rap with as battle rappers in a long gone previous life. I said, “How do you fancy being 17 years old again?” Much to my surprise, nobody said no. Somebody should have said no, but nobody said no. And we hadn’t rapped together for 27 years. But yeah, it was like a fish to water, really. It’s been an elephant in the room in my house. I don’t know how Jane [Weaver, Andy’s wife] feels about it. I go out walking every Thursday with a solid group of mates, as many as 20 walkers, and nobody talks about Andy’s rap record.

What effect did hip hop have on you as a kid?

Oh, man, it saved my life. When I started secondary school, I went to this vibrant landscape of goths, metallers, mods, psycho rockabillies, skins. It was brilliant. I seemed to be the only hip hop kid. Maybe one other. Five years later when you leave school, everyone was the same, everyone was into house music or Madchester.

A lot of my core group of friends, in later years following school, they really sort of fell apart. I’m from a nice area. It’s a middle-class, rural leafy area. It’s not The Bronx. But hard drug abuse really did heavily affect two of my core group of friends. And I didn’t even see it happen. But rap well kept me away from that. Totally kept me occupied. I was majorly addicted to buying records and making music. I used to work at the butcher’s, used to work at this factory, and I’d go out and buy the hip hop record. The next week, I’d be finding the original sample, and that’s all I did. I was just obsessed with doing that. It was everything.

And that’s how I learned to DJ, really. Because I didn’t have a disposable income, I was like, how can you afford to buy two copies of the same record? It’s so boring. So instead of buying two copies of the same record for doubling up, I’d buy the hip hop record and buy the original sample. So that was my USP, playing the original sample next to the hip hop record. And that was what got me gigs at Dry Bar and Haçienda, and noticed by what became the Fat City people. And then I was just playing, god knows, whether it be psych or Hungarian jazz or African records or whatever.

“Guru met me outside [the International 2]. He gave me a T-shirt and took me in the gig. I was Guru’s guest. How crazy is that? At that given minute, I said, ‘You know what? I’m never going to get a real job. This is me from now on.’”

So it all started very young for you.

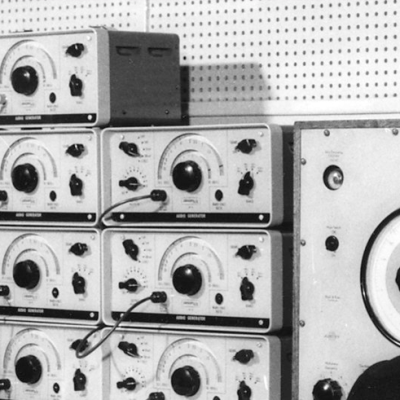

My dad was really encouraging. He taught me to make tape loops inside compact cassettes when I first got into LL Cool J. He also taught me how to control varispeed turntables using a Hornby power regulator off a model train track. So that’s how I’d learnt about the mechanics of music.

I was that one-off kid that used to go and play snooker on a Sunday night with my dad, and it clashed on with Leaky Fresh’s Out to Distress Rap Show in Manchester. I was in the car and I hadn’t seen my dad for a week. And I wasn’t that chatty, a bit agitated, and he was like, “What’s wrong?” I said, “Gang Starr are going to be on the radio tonight and I really, really want to listen to them being interviewed.”

My dad just said, “Well, why listen to the radio? Why don’t we just go down to the radio station and meet them?” And I was like, “That’s outrageous! We can’t do that!” And he goes, “Of course we can.” So he drove to Sunset Radio. He knocks on the door and Leaky Fresh said, “Yeah, no problem, just come upstairs.” So, I guess I was 16, maybe 15, I met DJ Premier, and I rapped my lyrics to Guru and Premier like that. Like, kamikaze style, you know, no self-awareness whatsoever. I just did it.

And I wasn’t even a confident kid. I was just so driven and confident in that medium. I wouldn’t have been able to ask out a girl to go to the pictures or something. I didn’t like standing up and reading in class. But the kamikaze mentality – it was just there. I’d never drunk beer at that point in my life. I’d never had sex. This was my outlet.

Anyway, Guru said to me, “Are you coming to the gig tomorrow night?” I said, “I’m not old enough.” And he said, “Well, don’t worry, I’ll put you on the guest list.” And the night after, at the International 2, Guru met me outside the gig. He gave me a T-shirt and he took me in the gig. I was Guru’s guest. How crazy is that? At that given minute, I said, you know what? I’m never going to get a real job. This is me from now on.

Amazing.

But what was beautiful as well that night, I got a job answering the phone for the radio station. And the second week I went, this local hip hop crew from Northwich had won a hip hop competition in Manchester, and they were called Violators of the English Language. This is Mark Rathbone: Boney Fresh. I met Boney and and he became my hip hop pen pal. I had a little studio at home that I’d made out of bits of old record players and whatnot. And he said, “Oh, we’ll come over and make some music.” So he brought his entire record collection to my house. There was like four seats in the car full of records and boxes. Got it, took us two hours to load it in, had a chat for an hour, and then he had to get back again.

And he tells me, ”At home, I’ve got a record shelf.” I’m like, “A what? How many records have you got where you need a shelf to put them on? You’ve got your own shelf?” Who knew years later he’d have filled two houses and he had to keep lockups away from his wife because he had secret stashes of too much vinyl, with like 20 copies of Remember My Song by Labi Siffre propping up the door.

So, we were basically our own switchboard for finding the original samples, and we just carried on digging and digging and digging and then making music together. And that became Violators of the English Language.

Who were your role models as far as British rap goes?

When I was leaving school, I’d turned my back on American hip hop and I was strictly into Britcore. And that was super niche. I mean, you couldn’t really buy much Britcore hip hop at places like Eastern Bloc or Spin Inn. You had to go to Piccadilly Records. And the Britcore: your Gunshot and Black Radical Mk II and Son Of Noise, that was filed with the punk. I think the common thread may be something like Tackhead or something which linked it all together. So even in Manchester, Britcore was hard to swallow for a lot of hip hop fans. And then things like that Low Life scene from Nottingham, and the next generation of Bristol hip hop.

Ruthless Rap Assassins must have been an inspiration?

I kind of separated Ruthless Rap Assassins from hip hop. They were their own thing. And in answer, yes, they were hugely inspirational. The sleeve to the Killer Album is one of my favourite sleeves of all time. It was a huge influence on the Badly Drawn Boy – Hour Of Bewilderbeast sleeve that I did. And the way the record was put together, with massive big samples of Beatles records next to radio stuff. I don’t even know if Ruthless Rap Assassins considered it a straight-up hip hop record. It was just a brilliant, brilliant mix tape.

They never influenced me as rappers. Whereas Krispy 3 from Chorley, they certainly influenced me as a rapper. There was a certain time in my life where Mikey D.O.N. from Krispy 3 was my Rakim. Even though it was hard to tell which one was him and his brother when they were on the record, because you know, a Chorley accent is a strong accent, right? Well, the fact that they never deviated from their accents was hugely important. And I will never, ever know how that was perceived outside of Manchester. Even outside of Preston.

“I didn’t like music. It was only when people started breaking the rules of music and destroying music that I became really interested. When sampling and scratching came out, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. This is brilliant. They’re totally ruining everything.“

Do you remember the first hip hop record you heard?

Well, I’d heard hip hop and tried to figure out what it was, and I remember being hugely confused. I think ‘Just Buggin’’ by Whistle and ‘Amityville (The House On The Hill)’ and all those sort of records. They weren’t just reappropriating James Brown, they were also reappropriating the Inspector Gadget theme. And as a kid, that meant something.

Up until that point I would go as far as saying I didn’t like music. I wasn’t a music fan. You remember when you’re watching The Muppet Show as a kid and then this music thing would come on, I’d be like, get it off, let’s get the puppets back on. I don’t want to see these weird American celebrities singing.

It was only when people started, to my eyes, breaking the rules of music and kind of destroying music that I became really interested. When sampling and scratching came out, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was like, this is brilliant. They’re totally ruining everything. You know, it’s great.

What was it about that, though?

I don’t know. I’ve definitely always been more interested in the mechanics of music, and I always hark back to when I was a kid, the fact you weren’t able to touch a record player. Mums and dads really treasured their records and kids weren’t allowed to touch the needle. You most certainly weren’t allowed to touch the surface of the record, right? You’re just going to ruin it or get electrocuted.

So when compact cassettes became omnipresent, slowly and surely, vinyl started to just be in the back of the cupboard. And in the early or mid-’80s nobody cared anymore, so I’d get all these records out. No one was telling me off any more. So I’m like, right, okay, I wonder what’d happen if you did scratch the record or if you played it backwards. And then the idea of putting Sellotape and Tipp-Ex on the groove and watching it jump back to the same point, to make loops. I was doing that without liking music whatsoever. I was just doing silly stuff. Sitting Star Wars figures on the records and watching them go around, and then wait until they crash into the needle and turning the speakers up really loud. Then to see someone like the Fat Boys or Run DMC do that on TV was incredible. I mean, that’s how I started.

And then as I got older and emotional, I started to love music. So, there’s always been that yin and yang, you know? The destruction and the emotion. As you get older and older, it’s really few and far between where you hear that piece of music which sets your heart on fire, because you’ve listened to so much stuff in your life. It’s still always there, that massive burst of energy in my heart. But on the most part I’ve always been looking for records that kind of sound wrong. If I could count my favourite records of all time, a high percentage of them would’ve started with a cringe.

That moment where you first heard Turkish psych and you’re like, That’s not right! Or when you first heard the German language on a Krautrock record. It’s just that little bit where things get wrong. Them crossovers from kosmische into disco or those crossovers from sort of ye-ye into symphonic rock or from country into folk and funk. You’re crossing a line that you shouldn’t cross. And personally it’s that first cringe moment that makes it become my favourite thing ever. There’s no other word for it rather than wrongness. I love wrongness in music.

So you started digging very young?

I was buying ’60s and ’70s records as a kid, and the code was pretty much look for anyone with an afro, and it’s probably going to have something funky on it. And then when you grow up and mature, you realise that, well, maybe the best hip hop records you bought this year sampled Frank Zappa or Jefferson Airplane or a cover of a Neil Young tune or a George Benson version of a Jefferson Airplane tune, and all those amazing records that came out of Chicago on Cadet-Concept, and all those sort of bands that they called mixed race at the time.

It’s almost like you got on a secret mission then, and there’s actually, what’s the phrase? – a You-can’t-judge-your-book-by-its-cover mentality. You don’t know, but on this record with the dude with a cowboy hat on the front is the biggest breakbeat you’re ever going to hear. And that’s really exciting. In your early 20s when you start to make those connections, it’s like, wow. This hobby could last my entire lifetime.

And at the same time you’re rapping and battling

I was that awkward kid at school who was kamikaze-ing off at girls’ 15th birthday parties getting the mic off the DJ to start rapping. My self-awareness hadn’t kicked in yet. We were Violators of the English Language, and we could do this. We could rap. We were good battle rappers. It’s accents, vocal tonality, upbringing, success notwithstanding. It’s a total previous life. People who have known me for 25 years remember me as a rapper.

And then it just ended quite quickly. Hip hop went into its purple period and stopped for a bit, and then came back 20 times harder, at which point I guess we’d all grown up and got proper jobs, or something that resembled that. I went to art school and that’s where I did meet people who were into rap. I met Rick Myers who’s a brilliant artist and graphic designer who in later years did all the artwork for Doves and Lamb. And a brilliant scratch DJ. And I met a guy called Derek Edwards who raps under the name Figure of Speech. So we actually had a crew by that point who would make records, make tracks every week, and we would make demos and send them to Cold Sweat and Music Of Life and all these independent hip hop labels.

So at that point, Violators of the English Language became a group, and we started to take it seriously to some degree. And we had enough original samples and stuff that people had never done before. Always made on two turntables, the old fashioned way. We were a graffiti crew as well, which was another big thing. When we left college, unfortunately one of us passed away and we started going our separate ways.

I was like a bar fly at Fat City Records which had just started up, and people kind of knew me at a lot of record shops in town: Out Of the Past, Rod and Caroline’s shop, Dean from Expansions, all the rare groove shops, they’d save records for me. I knew my way around town, got some DJ gigs with like I say [Manc arts impresario] Barney, Michael Barnes-Wynters who was hugely supportive. And then he got us a remix for Mr. Scruff. So, we remixed ‘Sea Mammal’ and we sampled an Ella Fitzgerald record, an Arthur Lee record, and Led Zeppelin and the Wicker Man soundtrack taped off the telly. It’s not bad for your first ever commitment to vinyl, is it?

So at that point, people were really interested in what we were doing, but they wanted nothing to do with the vocals. For some bizarre reason, they didn’t like the nasally Stopfordian accents that we were committing to these anthemic rap tunes.

Two or three months after that I became the designer at Fat City and Grand Central. So I had a job. And we’d go to places like Dublin, which was amazing, or Liverpool where I’d never been, and Marseille, and Düsseldorf. And that’s where I discovered Turkish records. I didn’t know what they were. For ages I was telling people to check out these Israeli sitar records because I was that stupid and young. In the same way that when I first found Welsh records, I thought they were Hungarian.

When you started digging for foreign language records, was that just coincidental or were you consciously trying to find more obscure stuff?

It became very obvious I was going to have to start hunting for strange noises and samples in odd records outside of my comfort zone. So I didn’t buy any English language or American language records at all, hardly. That was my rule. I’m not going to buy anything on a major label, and I’m not going to buy anything English language, because I had enough friends around me who did that anyway. Staying away from predetermined genres as well. I’m not trying to be stubborn, but music which is custom made for the dancefloor has never appealed to me. Trying to find the gaps in between genres is much more interesting. And then if you do find a country record or a Polish jazz record which just so happens to sound like a hip hop record or just so happens to sound like a house record or a disco record by mistake, that’s really exciting.

You start to learn stuff which you had no interest in your entire life in learning, like geography, politics, history. But when you discover Czech records and Polish records and East German records, which all came out on the same compilations, it’s just like, wow, I now have got some weird interest in communism. It’s amazing: in the same way that hip hop kept me away from my best friend’s drug habits, records in general have taught me about stuff that I never had any intention of learning

And it became not only a label, but a way of life.

The amount of times I’ve spent with people’s families in Poland through Finders Keepers, or going to stay at someone’s house for a weekend in the South of France and meeting someone’s widow or someone’s children. The record release almost becomes secondary, because as cheesy as it always sounds coming from a label owner’s tongue, there is a genuine family here.

There is a core group of people all over the world that help us, make connections for us. In the first records we did at Finders Keepers with Jean-Claude Vannier, he introduced us to loads of people in French studios. Just by hanging out with him and spending time with him, and not just chasing the signature on a contract and becoming a friend. This whole worldwide community that we’ve built through it has been a nice thing.

How did you go from finding records that hip hop producers had sampled to putting together your folk-funk collection Folk Is Not A Four Letter Word? What’s the trajectory?

That idiom, that lazy tag of folk funk, even at the time I found it hackish and a bit crappy. But it existed, and it’s exactly what it was. Because these were records which featured any number of attractive blonde girls on full frame record sleeves, but with Phil Upchurch playing bass or Bernard Purdey hanging out somewhere.

I’m never going to be able to tell stories where I was surrounded by music as a child. I just wasn’t at all. My dad had some fantastic records by John Renbourn and John Fahey and people like that, but he didn’t really like them. You know? Just his mates had told him to get them. But country and folk was a little bit around when I was a kid, so I could identify with that. And I’ve always been alright at reading the back of records and making connections. And that’s the Tetris mentality again. It all seemed fairly obvious to me that the folk funk thing was going to fill some weekend, you know? And it was really well received in Manchester.

You’ve also helped shine light on people that had been forgotten. To see people suddenly start maybe writing new music or gigging or whatever must be heartwarming. And you’ve done it quite a few times.

When a film like Searching For Sugar Man comes out and everyone says what an amazing story it is, well, it is truly an amazing story for something like that to happen. But there are many reissue labels where that happens every day. If you think of every band that didn’t make it, every band that got caught up in some political conflict or were excommunicated or didn’t meet the record label’s expectations. That difficult second album, or the demos that never made the cut, this could go on forever and ever and ever. It’s a beautiful, beautiful thing. Private press records made for people that have gone to the army. It’s just endless.

There’s obviously mathematically much more interest in music that hasn’t been released than has. If the music industry only releases 1% of all the music made in the world, there’s far more interesting music out there. It’s amazing to think what is between the cracks. And it’s only obvious that this stuff needs sharing, because there’s now an ability to share it.

The person who’s going to drop a heavy psych record in the middle of a full dancefloor where people have been listening to R&B, that person’s got balls. But you know what? In three or four years’ time, someone’s going to sample that record and you’ll all be listening to it in a totally different regurgitated way. It’s a fantastic thing, really. So, it just seems obvious for me.

I should mention the fact we’re headed to the football, which is why I’m here interviewing you, basically we’re actually both going to the same game today, which is Grimsby vs Stockport County.

Something I could never imagine myself committing to a microphone is the fact that I’ve recently got into football, having never been to a game previously in my life. Major League football, your Man Citys and Man Uniteds have got no interest to me. They’ve put me off football my entire life. But I didn’t realise there were private press football teams. I didn’t realise there were small football teams with a DIY punk aesthetic. I said to my son recently, “I’m never going to a football ground which is any less than 95% asbestos.” This is what I look for in music. You know, it’s the same thing. And I’m sure you agree with that mentality.

Yeah. I mean, it’s always puzzled me why someone could hate the Tories and buy really underground music but support Liverpool.

Makes no sense.

Whereas supporting Grimsby makes total sense to me. It is like I’m supporting a private press football team.

Absolutely, yeah. Exactly, yeah.

How do the compilations gestate? Like, say the Massiera compilation. Do you just end up amassing a certain amount of tracks and then you’re like, “We’ve got enough to do an album”? Or do you approach people and build it slowly? What’s the process?

Massiera is really interesting and a hugely influential person at the label, because he was a genuine enfant terrible. His history in sampling and stealing other people’s music early doors was truly brilliant. One of the first things I ever asked him was, how could you afford to get these early synthesisers? You know, pretty much at exactly the same time that pioneers like Pierre Henry and Jean-Jacques Perrey were using the same methods and the same very expensive tools. And he said, “Oh, I didn’t have any synthesisers. I just stole the noises off their records.”

And when you discover Joe Meek, they’re like two peas in the pod. They were destroying music early doors, which was in a very positive, anarchic and forward thinking way.

Massiera lived it. There’s so many sides to Massiera. After surf, he went into psych then he went into novelty records, then he went into disco. I didn’t even know, when he was still alive, how much hip hop stuff he produced, and I’m talking rapsploitation, I’m talking hip hop for the holiday makers in Nice that summer, but great stuff, and R&B and soul, and it still keeps on going. The question, where do you start with someone like Massiera? It seems achievable. You know. Massiera and Jean-Claude Vannier, there’s a finite number of tracks, you’d think. That’s exciting because you’ve made some sort of rules. You think you can do a pretty concise compilation of Massiera music. It is kind of achievable. And within that structure, exciting things can happen. When you do find one shard that you’d missed or something pops out the woodwork.

What I will say about Massiera, there’s probably things that he tried to sell to me then which I wasn’t interested in which I’m really interested in now. So he’s like, “Did you hear these breakdance records that I made?” And I was like, “No thanks.” And he’s like, “I did this thing in 1991 with these Native Americans.” And I was like, “No thanks.” And now I’m just like, ah, I really wish I’d listened more.

So you like to impose some kind of finite limit on your collecting?

I’ve got a hell of a lot of Bollywood records. 90% of them are horror soundtracks, right? When I decided to start buying Bollywood, I had to find a niche which was controllable. Or Italian library records, I only buy female composers. Because there has to be some rule, otherwise it just goes haywire. So there’s an achievable part. There’s an achievable way to do it, otherwise you’ll go mad.

I don’t want a record collection which is bigger than the house. I don’t want a record collection which only an accountant could have thought to buy. There has to be some sort of reality there.

It’s happened to you a million times, Bill, where someone said to you, “Will you have time in this lifetime to listen to all these records?” Well, no, of course you won’t. But you might have time to listen to all the female Italian composers. I only buy female punk now. I’ve got a hell of a lot of punk records, but now, if there’s not a girl involved, I’m not doing it – because I need to retain some sanity.

Any other rules? Like particular dates or periods?

I remember when I was buying funk at school, you’d read the date and if you saw 1982, you’d just throw it away. And then you realised later that a lot of the best records from Sri Lanka were all made in the ’90s, or a lot of great African stuff was made in these different eras you wouldn’t have expected. “What? That was made in the days of TV-am and The Clothes Show? It sounds like it was made in 1972.” Turkish music especially. It’s almost like 10 years out of date from what your ear’s accustomed to. It was foolish to dismiss things from the wrong dates early doors.

I’m really, really interested in private pressed post-rock now, because there’s some absolutely amazing stuff there. There’s so many bands that tried to imitate Stereolab when they came out, which just disappeared into nowhere. Just imagine.

Really? I had absolutely no idea that even existed.

I’m kind of regretting telling you.

I can delete it from the tape for a fee! When someone like Nas or Jay-Z comes to you for a sample, how does that benefit the label? Do you have publishing?

We don’t own publishing, but we have master rights. We have sync rights for stuff. There’s some stuff that we own. There’s some stuff we do own publishing for, yeah. We own bits of catalogue. So yeah. You just hope that …

I mean, are those sort of transactions things that help keep a label like yours afloat?

Yeah. What’s the phrase? Windfalls, I guess. We definitely don’t expect this to happen. We’ve never sat there and said, “Oh, don’t worry, mate. It won’t be long before Nas comes and samples us again.”

There was a time when only mods bought our stuff. Then people would be like, “Finders Keepers, oh, that Turkish record label.” So when it does repeatedly get embraced by hip hop, it’s great. There’s a big difference between some independent hip hop crew from Texas or mid-America or France or Hungary than there is to Jay-Z. When Jay-Z samples your record and denies it, and then you have to get a musicologist to prove the absolute obvious, well, yeah, that pays the bills. The artist on the label might get to wipe out the mortgage on his daughter’s house. Finders Keepers gets to pay a huge tax bill that we’d had hanging over ourselves for years.

Is it still fairly wild west out there?

I think doing things correctly, clearing samples, even meeting the original artists and having a full awareness of where this music comes from is part of the sport now. People want to do it right. The bootlegging thing and the mix tape culture and even the Ultimate Breaks and Beats thing that founded this whole culture couldn’t exist by today’s standards, because they’re missing out that component of the sport. Anyone can bootleg a record. You meet someone, “Oh, we’ve just done this compilation of brilliant Turkish psychedelic music,” or whatever. And it’s like, “Alright, did you get the rights to that?” “No, we’ve put it aside just in case they ever get in touch.” Well, you don’t qualify anymore. It’s not just about having your credit card, going on Discogs, getting a piece of music and sticking it on a compilation. There’s much more to it. The real record diggers are the guys that go that extra mile. The days of doing things wrong and illegally is bullshit.

And I think a lot of the best hip hop producers live by them rules, which is refreshing and good. The aesthetic of hanging someone out of a 40-storey window and watching the change come out the pockets is over. You know what I mean?

I love it when rappers get in touch with the original artists and the label. Czarface did it recently. And I’ve loved MF Doom and I loved 7L & Esoteric. I love that whole scene. That’s been with me most of my life. So for him to ring us and say, “Oh, we really want to sample this and we love what you do,” and they recognize it as a Finders Keepers record.

I’d got to the stage where so many people were coming to the label, whether it be Madlib or Action Bronson, or eventually people like Nas and Jay-Z, and then Kanye West coming for samples, which vindicated the subliminal reason why I set up the label in the first place. Because I’ll never stop listening to music with that tempo, without that sort of scavenger hunt sample mentality in my head.

Speaking of that, what’s the most you’ve ever spent on a record?

I’ve always said my interest in vinyl was more akin with scrap metal. Whoever came up with the phrase vinyl vulture, that encompassed everything really. When you start buying money, trophy hunting, you’re losing. You’re failing. It’s not why you ever did this in the first place, and you should be ashamed of yourself.

As a collector there’s a danger you end up forgetting that what you love is music and not the format.

I think we’re talking about trophy records here. Anything that’s on the wall and costs anything that resembles a month’s mortgage or an electricity bill is just totally inappropriate, especially in this day and age. This culture of people now going on the internet pairing very expensive bottles of wine with very expensive records is thoroughly inappropriate. You, like me, will go on social media and see a record which sounds good. You’ll click through and try and buy it and it’s 500 quid. That’s just game over. Inappropriate, boring. The fun’s been taken out. I’m very happy to say I’ve been out-priced from that game now. And there’s so many nuances in it, especially with jazz records, you know, music that was made to galvanise black communities in America in the early ’70s and now can only be afforded by white highfalutin accountants.

But trolling the pound bins will always be my game. It’s hard to go somewhere like Utrecht Record Fair and not be snow-blinded and get competitive and get into this knowledge battle about very rare records, because I can still do that, but the real trick is going and to not be distracted by that, and getting your hands dirty looking for stuff no one’s ever heard before and nobody even wants. And it’s still doable. I feel like we’re doing it a little bit now with the Occitan music. I’ve been doing it with Breton music for a while. These things are really exciting to me at the moment.

Final question. You’ve done a lot of things, worked with a lot of interesting people. What’s the proudest moment of your career?

The more I hear myself talking about the community and the family, I start to think I sound like Berry Gordy or somebody, but it’s really important, the family in Finders Keepers. We’ve got the pillars that are Jean-Claude Vannier and Suzanne Ciani. They are the king and queen of this label. And it’s a really beautiful thing that we can genuinely say they’re truly friends, confidants, and they’ve taught me lots about music.

There’s always bits of trouble around the corner, and there’s always gripes. But I have to say out of 200 artists, there’s probably only four people who’ve been awkward and a real pain in the ass, and three of them are from Manchester. So, other than that…

I guess I’m proud that we’ve stuck with it for so long. But it all does come back to the community and the alternative, almost imaginary musical landscape we’ve created. Jean-Claude Vannier is our Elvis and Suzanne Ciani is our let’s say Dolly Parton. Well, that’s it – we’ve created a whole alternative spectrum. There’s a whole alternative universe here which, when I’m feeling my lowest, I can look back on and go, “Wow, we’ve kind of rewritten something here.” Which is nice, right?

https://goldenlionsounds.bigcartel.com/product/gls013-magnetspro-verbs

https://www.finderskeepersrecords.com/

https://hypocriticalbeatdown.bandcamp.com/

https://www.nts.live/shows/andy-votel

© Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton