CLASSIC CLUBS: The Starck Club

703 McKinney Avenue, Dallas, 1984-89

In the backdraft of the disco era, in a city known more for oil and politics than wild club culture, one of history’s most unlikely nightclubs was born. Built by a kitchen extractor magnate and envisioned by future design legend Phillippe Starck – he of three-legged lemon-squeezer fame – Dallas’s Starck Club rivalled Studio 54 for its mix of the monied and the magnificent. And it owed much of its success to an unlimited supply of a new drug called ecstasy, which it sold legally over the bar.

For five years between 1984 and 1989, the Starck Club sat at the epicentre of Dallas nightlife, channelling the hedonism of Studio, the novelty of New York’s Mudd Club, the style of Le Palace in Paris, and the innovation of Manchester’s Hacienda. It pre-empted a new wave of US dancefloor culture powered by a brand-new drug, and embodied a wild and revolutionary spirit that made it like no other place in the world.

By the early eighties, mainstream disco was losing favour and while there were vibrant underground dance scenes around the US, most of America thrilled to Bruce Springsteen, Madonna and Michael Jackson. Dallas at that time was best known for the TV show of the same name, the Cowboys football team and the JFK assassination (probably in that order). But thanks to the vision of local businessman Blake Woodall, a nightspot opened that signalled a new chapter in American club culture.

The Starck brought together cutting-edge Eurocentric electronic music, new wave and acid house in a purpose-built setting designed by French architect and industrial designer Phillipe Starck. “It was uniquely perched at the nexus of money, sin, sexual politics, style, recreational chemicals, and strange new musical hybrids,” Dallas musician and video director Greg Synodis told Jeff Liles in the Dallas Observer. “The Starck Club influenced people’s tastes and acceptance of what was right or wrong.” A draw for anyone who landed in the city, nothing was off limits, including then-legal ecstasy aka X, key to the club’s success, but also at the heart of its downfall.

At the turn of the decade, Blake Woodall was looking for something a little more exciting than taking over the local, albeit highly profitable, Vent-A-Hood family kitchen extractor business. He decided to open a nightclub slap bang in the centre of his hometown. But knew it was no small undertaking. “There was a design aspect, a music aspect, a fashion aspect, management aspect,” Woodall told RBMA. He managed to pull in some big-name backers including Stevie Nicks, as well as younger investors like Christina de Limur (aka Sita) who connected him to a then-unknown industrial designer destined for greatness. “I brought Philippe Starck to the deal, built the Club – my official title: conceptual engineer – and was a night manager from ’84,” she explained. “The point of the whole thing was to bring a little Paris to Texas. Bring something exotic, something different. It was a gamble, but it was a gamble worth taking,” she told the Dallas Observer. “We were at the right place at the right time. Dallas was like a boomtown then.”

Having found the perfect location – under the Woodall-Rodgers freeway – Woodall left Starck to work his magic. All went smoothly until, part-way through construction, the Frenchman was called back to Paris to work on the French President’s residence. While seemingly frustrating, the breathing space proved serendipitous – financial daggers had been drawn as costs ballooned, and while he was awaiting Starck’s return, Woodall paid a trip to Ibiza. “I was awed by the culture, the fashion and the music, and how it seemed so international,” he recalled. “We were listening to music from Barcelona, Munich, Tokyo, New York, Los Angeles. It was a remarkable music scene, and I made the decision at that point that would be the music aspect of our project.”

Before the grand opening night, a couple of jigsaw pieces were still missing. The first was Door Bitch. Woodall recruited the ‘Parisian Queen of Punk’, the late Edwige Belmore, doorwoman at Le Palace and frontwoman of Mathématiques Modernes who would turn away punters even when the dancefloor was half-empty. “I loved the original door girl,” Starck DJ Mark Ridlen remembered. “She would be doing the Watusi to my random mix one minute, and the next be manhandling an unruly cokehead to the nearest exit.”

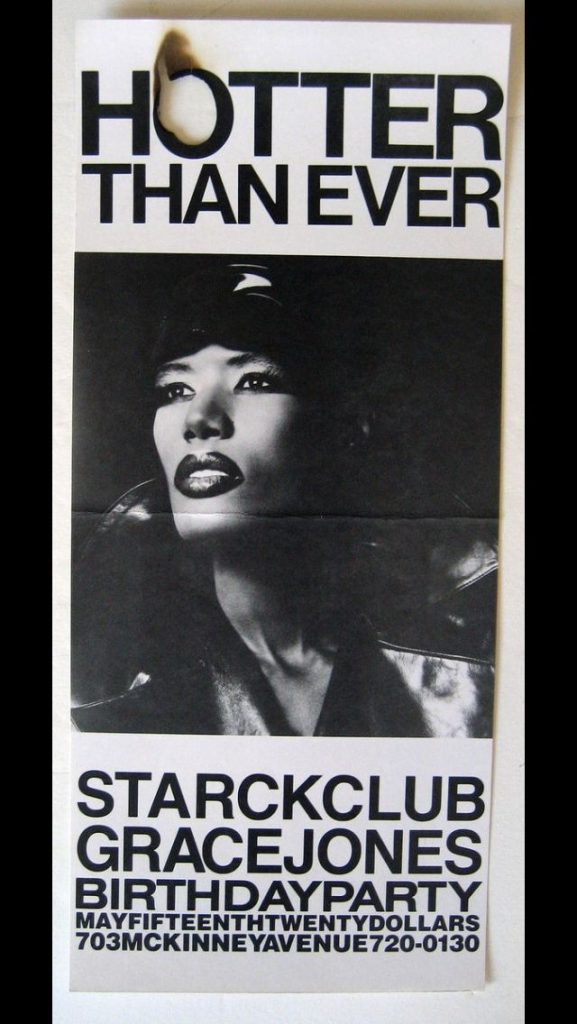

The other was, of course, the music. With an opening night set to feature Stevie Nicks, Grace Jones and the Dallas Symphony Orchestra performing live, Starck recruited compatriot Philippe Krootchey on the decks. A model for Pierre and Gilles’ and a permanent fixture in the Paris clubs, Krootchey was also a musician, releasing ‘Dance on the Groove (And Do The Funk)’ as part of Love International. However, after many delays he failed to made it to the Starck’s opening night. Instead, on the advice of Grace Jones’ manager, at the last minute they pulled in New York-based Kerry Jaggers, who would be resident for the next six months.

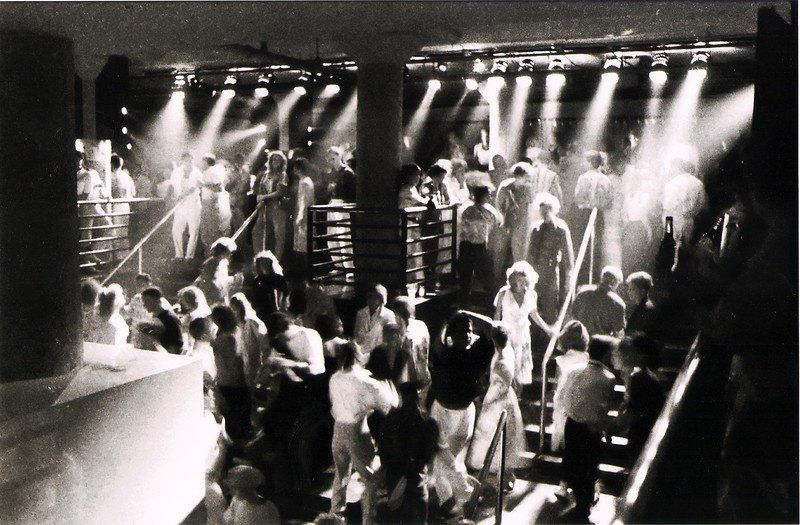

The Dallas Morning News described the opening night as the kind of party Jay Gatsby might have thrown. To the fore was Starck’s radical design. A marble staircase led to a colossal bisected circular door which by all accounts took some welly to get open. “Once you entered beyond the red velvet curtain, it was an amazing labyrinth of walkways and hallways of a shrouded interior made up of translucent white curtains which made up cubicles,” remembered a patron on DiscoMusic.com. Kubrickian in essence.

But it was the dancefloor that really wowed the crowd. Sunk 12 feet below the DJ booth, the dancefloor housed the subwoofers, creating the sensation of actually being inside the sound system. And the floor was bisected by a giant arch which was placed there provocatively to create division. “It was the Capulets and the Montagues,” David Muir, another Starck DJ and regular told RBMA. “We didn’t go over and dance on that side and they didn’t come over and dance on our side. It was two separate worlds.” The other great talking point was the unisex bathroom. With stalls divided by glass blocks and motion sensitive TVs, people were very much left to do what they wanted. “There were honestly people that came into that club, went to the bathroom, stayed for two and a half hours, and when they left the bathroom went home,” General Manager Greg McCone added. “Never even went in the club.”

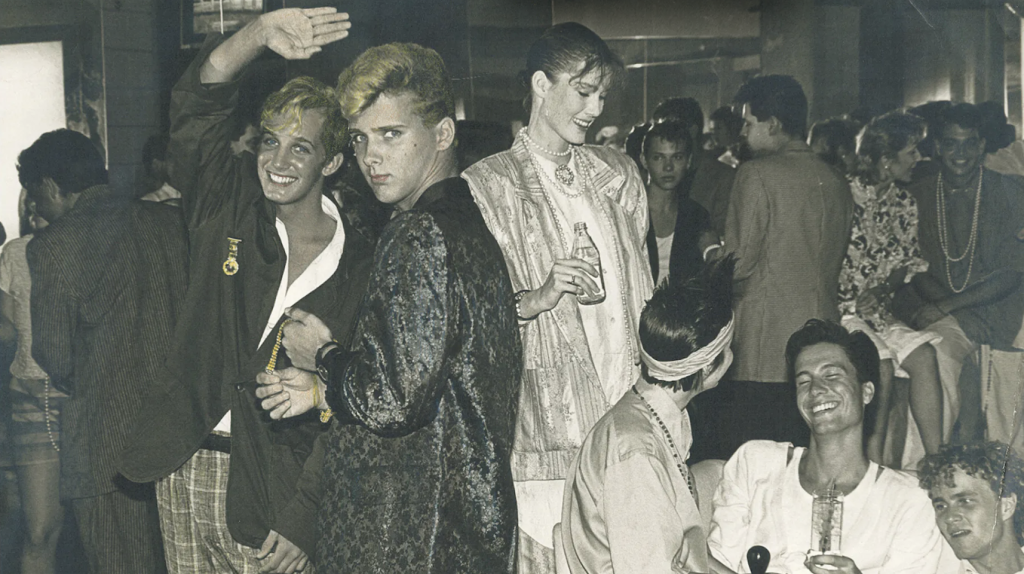

Despite the extravagant opening night, it took a while for word to spread. A strict door policy was in place, as much to protect the patrons as to create hype. “If you were of the gay culture you would want to know you were welcome,” Woodall explained. “If you were a business guy you would want to know you’re welcome. I had this idea that inside there would be green hair and then there would be some of the most remarkable, political people in the world.” In Dallas at that time, to have a dancefloor where drag queens rubbed shoulders with celebrities and aspiring politicos marked a truly watershed moment – all inhibitions and pre-conceptions to be left at the door. “There’d never been a mix of straight and gay crowds in a dance club, and it was just open season,” patron and doorman Nick Hamblen told the Dallas Observer. “I’m gay, and it was nice to go to a bar that was so incredibly mixed. The Starck Club opened the door and we never turned back.”

The dynamic of the place encouraged a broader, wilder and more creative crowd. “Part of the design and desire was to have a complete mix of all spectrums of people,” David Hynds, who ran the club’s art dept. told D Magazine. “The club was so ahead of its time, a Saturday night looked like Halloween,” remembered McCone. “People were in drag as Marie Antoinette or dressed up in tight suits painted green like Mars men. They’d come in naked with a terrycloth bathrobe on.” The club hosted fashion shows, plays, performance art. Local artists were invited in and there was an anything goes attitude. “We had these funky theme parties,” Ridlen told D Magazine. “We would make it look like a grocery store or we would make it look like a rodeo. We’d have these fun themes with appropriate music. We’d always have video exhibits, people showing their art videos. We had events just for that.”

Word quickly spread that the Starck was the hottest place in town, and by the time Grace Jones returned a couple of months later, it was the final push that was needed. Jones arrived late, very late, and insisted that the air conditioning was turned off. But she dazzled the crowd. And soon the Starck was a must for any celebrity who happened to be in Dallas – Rob Lowe, Robert Plant, Annie Lennox, Tom Cruise and Prince were all spotted. A Young Republicans fundraiser was held there with future prez George W Bush in tow. Thanks to its futuristic design, the club even featured in classic ’80s dystopian sci-fi Robocop!

The club’s other secret weapon was, famously, ecstasy. In 1984, when DJ Kerry Jaggers arrived from New York a friend gave him some with the instruction: “Spread that around. It will make it more fun.” Still legal in the US, ecstasy was made freely available at the Starck, sold by the bartenders who proudly advertised their side hustle with the t-shirt slogan “I got X.” “The money was crazy,” bartender Craig Depoi told the Dallas Observer. “Every night I’d make 600 to 800 bucks. People would slide ten or twenty hits of legal X across the bar in matchbooks.” The drug’s abundance was thanks to the crusader-like efforts of Michael Clegg, one of a group of Boston chemists who had investigated the therapeutic benefits of the drug and gone on to become one of its key producers (as well as rebranding it from Empathy to Ecstasy). Though now legendary for it, the Starck was not alone. “It was easy and clean, and all of the clubs in town were making it available to their clientele,” Mike Graff told Liles. “The whole city was overtaken by this phenomenon,” Wade Hampton told RBMA. “Southern Methodist University was completely knee-deep in ecstasy. You’ve got the children of politicians and you’ve got the parents trying to see what the kids are up to – it wasn’t unusual to see your parent’s friends out at Starck.”

As well as Grace Jones and Stevie Nicks, live gigs included Kid Creole and the Coconuts and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but the Starck wasn’t really set up for live music. The stage was encumbered with large pillars, the acoustics were all wrong and the audience was thirty feet below. Unsurprisingly then, when it came to music it was all about the men behind the decks.

Despite failing to make the opening night, Frenchman Phillipe Krootchey was an early resident, but his punky approach meant he didn’t last long. “He would play something three times in a row and kind of sloppily scratch, throw people off in their rhythm while they were dancing. People would boo, and I thought, ‘That’s great!’” Mark Ridlen told the Dallas Observer.

Ridlen himself also played there, adopting a similarly raucous, anything-goes style. “He had more of this punchy flavour that was probably more suited for the bombastic desires of a Dallas crowd,” says Wade Hampton, producer of the unreleased documentary The Starck Project.

Kerry Jaggers brought a style of DJing that wasn’t bound to four to the floor. “We weren’t afraid of playing below 110 beats per minute,” he recalled to RBMA. “Most DJs would say, ‘Oh, no, that’s too slow. You can’t play that in a club!’” He didn’t shy away from playing more commercial tracks either – The Smiths’ ‘How Soon Is Now’, Billy Idol’s ‘Eyes Without A Face’ and even Nik Kershaw were aired there.

It was his successor, San Antonian DJ Rick Squillante, who put The Starck on the map musically. “Rick was a very Hawaiian shirt and flip-flops type of guy,” said Jaggers, who brought him to the Starck. “I had to kind of trick them together, but that was one of the best things that I probably ever did to that club.” Squillante would go on to head Virgin Records New York dance division in the ’90s, signing key tracks by Josh Wink and Armand Van Helden and helming Janet Jackson’s rise to superstar status. In Dallas, playing what became known as “Starck music”, Squillante brought a mix of deep disco, new wave and European synthpop to the club. He played Trevor Horn, Pet Shop Boys, Echo & the Bunnymen, Bauhaus and Malcolm McLaren – music that the Starck crowd had never heard before. They called it “Eurotech”. “He was playing music you couldn’t hear at any other local club… that you couldn’t hear at any other club in America – until he made it relevant,” Don Nedler, who (briefly) reopened the club in 1996, told the Dallas Observer. But while he may have had the crowd eating out of his hand, Squillante wasn’t what you would call a technician. He didn’t really mix, preferring to spend his time hosting breakaway parties in his booth. But he was always in control, deftly switching between tracks and often playing for ten or eleven hours straight. “Rick would be talking to all these people and would turn away with 30 seconds left of music, walk over, pull a record out, throw it on, and it would be right on cue and mix right into a new track,” Starck regular David Muir told RBMA.

As the eighties advanced so did the music, and while Squillante was highly lauded, his successor, “GoGo” Mike DuPriest was perhaps even more influential. Embracing acid house and the burgeoning rave culture, he shifted from the melody aesthetic of Squillante to the pulsating rhythm of house music. Often using three turntables, DuPriest acted as the inspiration for many local DJs who took the new music and spread it across the US – Red Eye, Rob Vaughan, Cle Acklin, JT Donaldson, DJ Merritt, Ronnie Bruno and DJ Daisy – moved by his unmatched knowledge for this new music and flawless choice of records. “Chicago house tracks by Frankie Knuckles and Fast Eddie, Detroit Techno tracks from Derrick May and Juan Atkins alongside UK Acid House artists like 808 State, S’ Express, Baby Ford and The Beatmasters,” Jeff K told Liles in 2009. “Having come to Dallas from NYC, Mike DuPriest had the knowledge of these records and understood the movement that was upon us.” And it wasn’t just his choice in tunes; it was a whole new approach to playing music. “He was also blessed with the skill and technique to phrase, mix and generate emotion unlike any DJ I’d ever seen before,” continues Jeff K. “Prior to Starck, electronic dance music had never made me cry. That final night of Starck Club with Mike DuPriest at the helm, I wept like a child.”

All good things must come to an end and by 1986 the writing was on the wall. This was partly down to the fact the Starck was so fun, innovative and audacious that it had spawned a wealth of new clubs in Dallas and its novelty was diminished. It was also partly down to MDMA. The Club’s open drug sales meant the DEA got very antsy about it. MDMA became a Schedule 1 narcotic on July 1st, 1985, and a year later the Starck was raided. The club was served with a no-dance ban in April 1987 which they embraced by running a “No Dance” party. It carried on for a while but following one last hurrah with who else but Grace Jones, it closed its doors on July 11 1989.

“It was fun being one of the owners of one of the most remarkable nightclubs in the world,” Blake Woodall told RMBA. “Then I started seeing how big it was getting, how almost out of control it was.” Christina de Limur agrees. “All these things do have a lifespan. We had a good run.”

© Sarah Gregory