Alex Rosner broke the sound barriers

Probably the most influential figure in the history of nightclub audio, Alex Rosner devised the approach that survives to this day. Among his creations is the first stereo club mixer, a custom piece used to great effect at The Haven by the groundbreaking Francis Grasso. And with the Loft’s David Mancuso, he devised the tweeter array – those clusters of high-frequency speakers that hang from the ceiling. Born in Warsaw, he and his father were held prisoner in German concentration camps, and only escaped death thanks to their musical abilities. He came to America aged 12 unable to read or write but eventually qualified as an engineer. He was driven by a powerful belief in the superiority of recorded music, and ignited by the diversity and togetherness he found in New York’s nascent disco scene. After a long career building sound systems for the city’s most influential clubs, he transferred his ideas into improving sound for places of worship.

Interviewed by Bill, in New York, 5.10.98

How did you get involved in building sound systems?

It was not my intention to build sound systems. I was having dinner one night in a restaurant, and there was actually a discotheque and the sound was terrible, so I put down on my card “Your sound stinks” and put it under an ashtray. My best friend, who I was with at the time, when I got up to get my wife’s coat, he took the card and handed it to the owner. And the owner came up to me and said, “You’re right! Can you come and help me?”

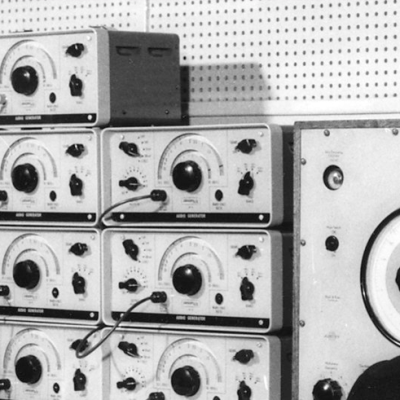

It was called Andiron in Flushing, Queens. From there I met somebody at the World’s Fair in 1965 where I built the first stereophonic disco system. Up until then it had all been mono. There was no equipment available at the time. There were no mixers; no stereo mixers; no cueing devices. Nothing. I had to invent the wheel until the Bozak mixer came along. And I helped Bozak design his mixer; I gave him suggestions so he could make it better. And that was the standard in the industry for a while until the Urei came along.

When did the Bozak come in?

In 1968, around about. Louis Bozak, he passed away recently.

What prompted him to devise it?

He didn’t devise it either. He already had a ten-channel input mixer. I suggested to him that he only needed to make minor modifications to this unit make into a stereophonic disco mixer. And he thought it was a good idea, so he did it. And right off the bat he did it the right way. That became the standard and he only modified it once. It stayed for ten, fifteen years.

What was your interest in sound?

I was a sound engineer, but it was my hobby. At the time I was working as an engineer (for some company I can’t decipher) in the defence industry. And audio was my hobby. But by 1967 I quit my job and went into building sound systems full time.

Construct the sound systems for clubs?

Yeah. I mean, I used existing amplifiers and existing loudspeakers and turntables that were on the market. But the cueing devices and mixers were not available so I had to sort of build them from scratch.

What existing equipment were you using?

For turntables we were using Thorens TD-124, the standard of the industry at that time, it had a quick-start. You slide the lever and it lifts up the plate and stops the record. It was primitive but effective. The problem with that turntable was that there was a lot rumble. So for stereophonic application it wasn’t so good. It was only when the TD-125 came along later that was much better; and they came up with other techniques, like direct-drive. Then that became standard for turntables. So far as pre-amps and mixers, the Bozak was the standard, and before that I used one that I had developed, which was a real primitive arrangement.

Your first mixer was a simple flick switch,?

Right, it was a switch with a couple of levers which were faders. And then it had another switch which gave you an output from each channel so you can cue up on either turntable regardless of which one was being fed to the dancefloor. For amplifiers we used Macintosh which was very high quality. One of the early systems used two Macintosh units, it was called the model 275 I remember. It worked; it was very effective. The loudspeakers were by Altec. Then JBL came in shortly thereafter, and I used their loudspeakers.

Which were the first systems you constructed?

The first one was at the New York World’s Fair in 1965. For the Canada Pavilion and the Carnival Pavilion. One was called Carnival-A-Go-Go and the other Canada-A-Go-Go.

They were specifically made for music?

They were playing rhythm and blues, all kinds. Anything that people would dance to.

They were operated by disc jockeys? Anybody noteworthy?

Yes, but nobody noteworthy.

Where was your first club system?

The first was the Ginza, like the Ginza in China. The owner was Richard Chu. He had built the system himself, because he was an engineer. He invited me to come and listen to the system. Which I did and I pointed out to him that it had a mono Altec mixer. In those days the standard in the industry before Bozak was the Altec 1567-A and that was a mono mixer with no cueing provisions. It was nice and good sounding, but he only had one amplifier, so when I told him he needed to make some modifications for reliability purposes, he kind of laughed at me. I was embarrassed and left.

About three months later, he called me in the middle of the night. The system had died and could I come and help him. He was rather in a panic. I’ll never forget this, because it was a very important lesson in reliability for me. This is a pivotal moment that you could say inspired me to get into this business. This was still 1965, maybe ’66. Anyway, I got down there in about 20 minutes and when I walked in the place was deserted. The dancing girls were up in these little cages, they were sitting there with their legs dangling out and just not doing much. There was a couple sitting at the bar. And this man, who was normally very calm, was very excited and very nervous, and he asked me whether I could fix this as quick as possible.

So sure enough the amplifier that he had, even though it was an excellent amplifier, had a blown internal fuse; I guess it was a bad tube. So I walked in there with a tube caddy, in those days service-men carried a tube caddie. In the other hand I had a tool case. I put a new fuse in, I put two new tubes in, I got it working. It was about half hour roughly from when I walked in. It was difficult to work because these girls were very pretty and it was distracting. I had to sit right next to them with hardly any clothes. And I was kind of a square guy; I wasn’t used to this.

Finally, when I was finished, he was so grateful and he started to calm down and I couldn’t resist it: “Mr. Chiu, why are you so excited? You’re lucky. It’s a Wednesday night, there’s nobody here. If it was a Saturday night I could understand you being excited but there’s nobody here what’s the problem?” He got about two inches from my face and said, “When I called you at one o’clock this morning, this place was packed with people. The business I lost tonight, I could’ve bought a new system.” When I heard that, the image in my mind was like a chariot in a desert in war-time. And the chariot was the sound system and it could not stop. You had to build in such a way that there were enough horses in front, so that if a horse died you could chop it loose and keep going. You’d have concentric wheels on the hub so that if a wheel broke, another wheel would carry its weight. And under no circumstances could the chariot stop because if it stopped, you get shot and you’re dead. That was the image. I resolved from that point on… It became a high stakes game. He hired me to do the entire system, so that was the first one I did. Thirty years later, we’re now talking about 400 or 500 systems.

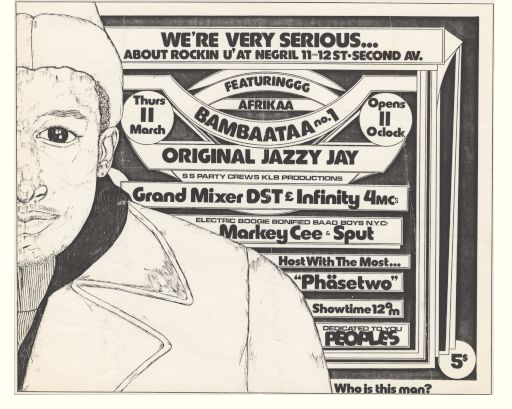

So how did you come across Francis Grasso?

I met him at some club he was playing at. I don’t know whether it was a club where I did the sound system or not. I never hung out in clubs where I did put in the sound system. I’d go to clubs where I didn’t. I’d persuade the owner that he needed a proper sound system and I would get in and… what I always remember, Francis played in that club or he played in the club after I got through with it.

You installed the system at the Sanctuary didn’t you?

Yes.

Wasn’t that the first place where Francis had had some kind of cueing system? He worked at the Haven before that.

I did the Haven too. The cueing system was one of my old-fashioned adventures. They called it the Rosie because it was painted red. It was really primitive. And not very good.

But it did the job?

It did the job. Nobody could complain because there was nothing else around.

What was the difference with the Sanctuary? [Pioneering DJ and sound engineer] Steve D’Acquisto said it was so much better than anything that was around at the time.

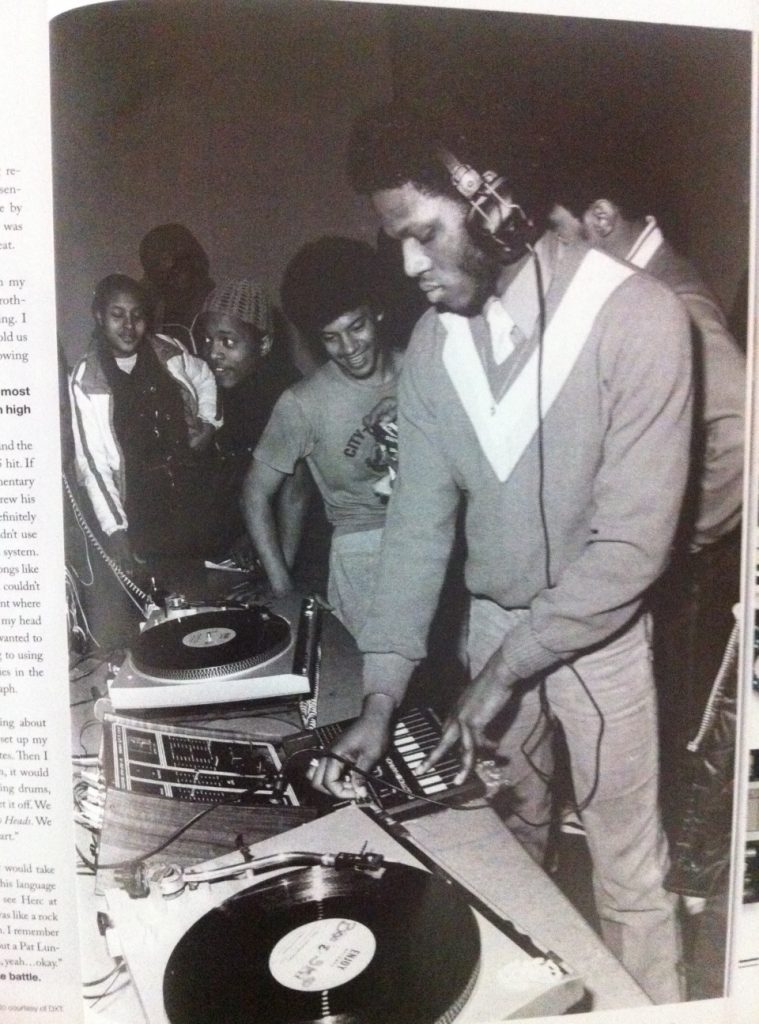

It’s just a matter of quality. See, I was an audiophile. I applied audiophile techniques – hi-fidelity – to commercial sound which, until then, had never been done. Most commercial sound systems sounded lousy. I made it sound good by putting in good components; there were no secrets. It was just a matter of persuading the owner that he had to spend the money to up the ante and put in the proper components. I knew where to put the loudspeakers. I knew how many to use and make it sound good. After that, little by little, I started using sub-woofers and tweeter-arrays. The tweeter-arrays were actually David [Mancuso]’s idea. He told me to build them and I said I didn’t think it was a good idea. He said, “I don’t care what you think, just make it anyway.” And I did and it was a wonderful idea.

Where does the name tweeter come from?

A tweeter’s what you call a high frequency transducer, that plays high frequency sound.

So it was an existing term already?

Right. A tweeter-array is where you have a tweeter facing north, south, east and west. Basically you have four of them in some kind of enclosure so that all four are mounted like a chandelier above the dancefloor. And that idea was David’s.

You thought it wouldn’t work. Why?

I didn’t think was a bad idea, I thought it was too much. He wanted two of them which would have been eight tweeters and normally in a sound system, there’s one tweeter per channel and he wanted eight. I thought it would be too much high frequency, but I was wrong. It was so high up, that’s not where the pain level is. That’s not where the hardness is. The more you have up there the better. So it was actually a terrific idea. How he got inspired to think of it, you would have to ask him. I had this fellow, Angelo Di Guiseppe, he physically built the wooden enclosures for it and I got four JBL tweeters and I put them in there. Crossover at that time was about 5kHz and it worked great. From there on, I used it in every club I worked in.

Do you remember when this was?

Yeah, I’d say it was 1971.

How did you come across David Mancuso?

I was introduced by a mutual friend. He said I should stop by and look at his club, because I could be some service to him. Which I was. I rebuilt his club for him, and made his sound much better. He had what was basically a home system. When I got through with it, it was a disco system. When I first went to his club and saw the excitement and energy there, it was very inspirational to me. At that point I thought discos were a wonderful idea. That there was a mix of sexual-orientation, there was a mix of races, mix of economic groups. There was a real mix, where the common denominator was music. I thought that was good thing. I remember ripping off my shirt and dancing. I loved the music. It was the real stuff. It was terrific and at that time I was in between wives and it was the right time.

From there where did you go?

I don’t really remember the names of the clubs, but after there were a lot and they came quite quick. Many of them were gay clubs. The gay club owners were willing to put their money where their mouth was. And they were willing to invest in high quality sound systems. These were relatively small clubs but it was before Studio 54. I never really liked clubs like that. The largest club I ever did was the Copacabana and that was much later and that club went for a long, long time and in fact is still in business but on a different site. The real big clubs like Studio 54 and the Paradise Garage… The Paradise Garage I did the actual original design and Richard Long, he and the owner became lovers, and I guess he took the job away from me.

You didn’t actually install the system then?

No. I did the preliminary design. And he did the installation.

What other elements did you install in the Loft that made it different?

It was the way it was configured. I put in Klipschorns and I bi-amplified it; tri-amplified it. And at that time that was something new that wasn’t done. It was just the way it was configured. Even today, even though David knows a lot about sound, he calls me and asks me to make final adjustments. It’s subtle aspects of the balance, you might say, that made that place sound good.

Why were you so good at this?

I knew what reproduced sound was supposed to sound like. My whole family were musicians. I played several instruments. I knew what orchestral music was supposed to sound like when amplified. That knowledge helped to me to set these systems up so they would sound proper. Since I knew electronics – I’m a graduate electronics engineer – I was able to make the connection. And that really was what qualified me, plus there was a tremendous interest. I really liked it. To this day I like the concept of the discotheque. I like the concept of reproduced music as opposed to live music. And I thought that technology was available to make things sound good and sound realistic. I experimented a lot.

At the World’s Fair I had make this acoustically transparent curtain, so that it would sound like an orchestra playing behind the curtain. But what I didn’t realise at the time, is that the audience actually prefers to be enveloped in the music, as opposed to being hit from one direction, which an orchestra would do. But an orchestra is a live phenomenon and the liveness makes up for the fact that the music does not surround them. So when the orchestra is not there, and you only have the loudspeakers, no matter how realistic they are it turns out it’s better to wrap people around with loudspeakers rather than have them only coming from one area. Although coming from one is very realistic, because it does sound like this orchestra behind the curtain. That can be done. And I did it. Some of the selections, it really sounded like the orchestra was right on stage.

Later on, after the World’s Fair, I realised it was better to have the sound around so I developed a technique to surround the audience with mid-range loudspeakers with the bass speakers on the floor. And two flying tweeter-arrays over the dancefloor. And that four-way arrangement: the tweeters are one; upper and lower mid-range is three and bass speakers is four. With four separate amplified sections and an electronic crossover network. That’s what became the standard of the industry and I wrote a technical paper for the Audio Engineering Society Convention which I read and got published. It was the only paper on disco that was ever published in the journal. And that’s how it became the standard. Everybody took that as the bible and everyone just took those ideas and went with them. And today there isn’t a club that doesn’t have tweeter-arrays.

When was this paper published? Is it possible to get it from a library?

I have a copies. It was published in the journal of the Audio Engineering Society. If you hold on a moment I’ll look up the date on it. July 1979.

What was your inspiration? Just being a fan of music?

Yeah. At that time I was into Latin music. Latin music was somewhat related to black music and African music and jazz. That was something I was really into and that wasn’t far from black music. It was a natural transition. And it didn’t hurt that my girlfriend – now my wife – was black.

Do you think Mancuso was influential because he was both music fan and audiophile?

That’s right. No question about it. The sound system is just a tool in the hands of the artist. But without the tool, the artist can’t do too much. The tool in the hands of a lousy artist, is a lousy machine. You need both to make it successful. David Mancuso and… I can’t think of his name

[Bill runs through the first generation of disco DJs] Michael Cappello? Steve D’Acquisto? Francis Grasso? Nicky Siano? Walter Gibbons?

Walter Gibbons. I did Galaxy 21, too. All the guys you mentioned, I did all their clubs.

You’re still installing sound systems?

Yeah, but in the last ten years I’ve been mostly installing systems in houses of worship. It just evolved that way. The premier churches. I’ve just finished Trinity Church downtown. They need sound systems so they can be heard by their parishioners.

That’s a nice coincidence, since people like D’Acquisto often talk about those early clubs being like places of worship.

No question about it. It was a spiritual experience. I really can’t describe it. It was truly inspirational. There was a lot to it. There was a guy named George Freeman who had a club where Walter Gibbons played, Galaxy 21, and he often talked about that. He said it was a spiritual experience. He said he was providing a venue for a spiritual experience. When I said that, I said, yeah, that’s not far off.

I remember him making me install a volume control so that Walter couldn’t play too loud. There was a hidden volume control in his office. When Walter found out he quit. So I got Walter to come back and they kissed and made up. I tried to talk the owner out of putting this volume control in. I said you should talk to Walter and agree on sound levels. George Freeman says, “No, no, Walter doesn’t agree with me and I’m the boss and I own this club and I pay you to fix this sound system, so you do as I say.” So I put it in, then Walter quit and all the people went with him. George had no business, so he had to get Walter back and get rid of the volume control. True story!

How long was he gone?

About a week.

Very quick then.

Yeah. It was a bad idea. You can’t take the gas pedal away from the driver.

Who were your favourite DJs from that period?

Nicky Siano was terrific. I loved him.

Why was he better?

He built excitement. Same with Walter. And of course, David [Mancuso]. And Steve D’Acquisto, he worked at this club Tamberlaine. I built the system there. They just knew how to build excitement without making the music overly loud, they played beautiful, exciting music. They got people really excited on the dancefloor and happy to be there and want to come back. They knew how to do it. It was done with music. It wasn’t done with mirrors and smoke.

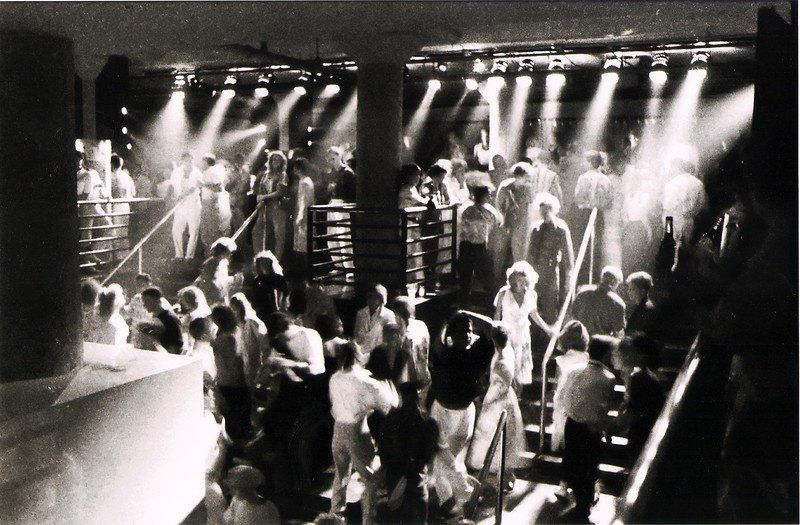

They didn’t do it with lights, believe me, the lighting systems there were very limited. I learned through experience, there were no schools for these things. I did a club called Tuesday, a jazz club. On opening night the lights failed. And the owner took a 200watt light bulb, put it on an extension cord – it was one of these work lights – and he plugged it upstairs in the bar and hung it in the corner of the room. And the party went on like nothing happened. I just scratched my head and thought, “Gee, can you imagine what would’ve happened if the sound system had failed?” So the lighting fails and nothing happened. That’s when I realised that the lighting wasn’t important. It wasn’t the meal, it was the dessert. It was not an essential ingredient in the club.

So I always told the owners, listen, “If you’re low on money, put in a decent sound system and put in whatever lighting you can. You can always improve the lighting later.” What makes the club is the sound system. I never put in a lousy sound system. I was always able to persuade the owners to put up the money to have a decent sound system. Richard Long was the only one that did decent quality work at that time. All the others were cheap stuff. Richard befriended the rich gay owners and he started doing really big clubs. He did a few clubs here and a couple of the clubs he didn’t do so well, so I had to go in and re-do them. That’s how it was.

Do you feel lucky that you were the right guy in the place at the right time?

Yeah. I guess I did. I had a good time. I made money and I established myself in business. There was a period when I primarily did discotheques, though I did do other things, like restaurants, auditoriums and homes for wealthy people who wanted nice quality sound. As disco started to die I did more schools, home theatres and then the church market opened up. Jewish temples, Catholic churches. There isn’t a religion I haven’t done. Now I’m doing a mosque.

© Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton